The federal Superfund Program was created in 1980 to respond to releases of hazardous substances in the environment. The Superfund Program protects the public and the environment, making communities safer, healthier, and more economically viable.

Superfund sites are some of the most significant and expensive sites of environmental contamination. Superfund sites include all sites in the United States where the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified contamination with hazardous waste. When the EPA determines that a site requires cleanup, the site is placed on the National Priorities List (NPL). As of 2017, Michigan has 65 sites listed on the NPL. An additional 19 sites that were previously on the NPL have been deleted because all necessary response actions were completed.

NPL sites fit within three categories:

- Proposed NPL site,

- Current NPL site, and

- Deleted NPL site.

A proposed NPL site means that hazardous substances have been identified at the site, and it has been recommended to the federal Superfund Program for clean-up. Current NPL sites are those that have been accepted by the Superfund Program and are undergoing clean-up. The deleted NPL sites are those that have completed the process of clean-up, and they have been deemed protective of public health, and the environment.

Sites in the Superfund Program may be managed in a variety of ways. The EPA, the state, or private parties may implement the cleanup. The Superfund law allows for enforcement actions which make private parties conduct the cleanup if they were responsible for the contamination. Where there are responsible parties, the EPA may take the enforcement lead with the state providing support (36 sites in Michigan). In some cases, the state may take the enforcement lead on particular sites (10 sites in Michigan).

The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality also has sites for remediation called Baseline Environmental Assessments (BEA). BEA sites are facilities with a history of use of chemicals. The sites may be classified into several categories, including Part 201 (i.e., having one or more contaminants) and Part 213 (i.e., having leaking underground storage tanks). Remediation of these sites includes activities to manage and reduce risks of environmental contamination. This may be achieved through activities such as: initial evaluation, interim response, remedial investigation, land and resource use restrictions, and monitoring.

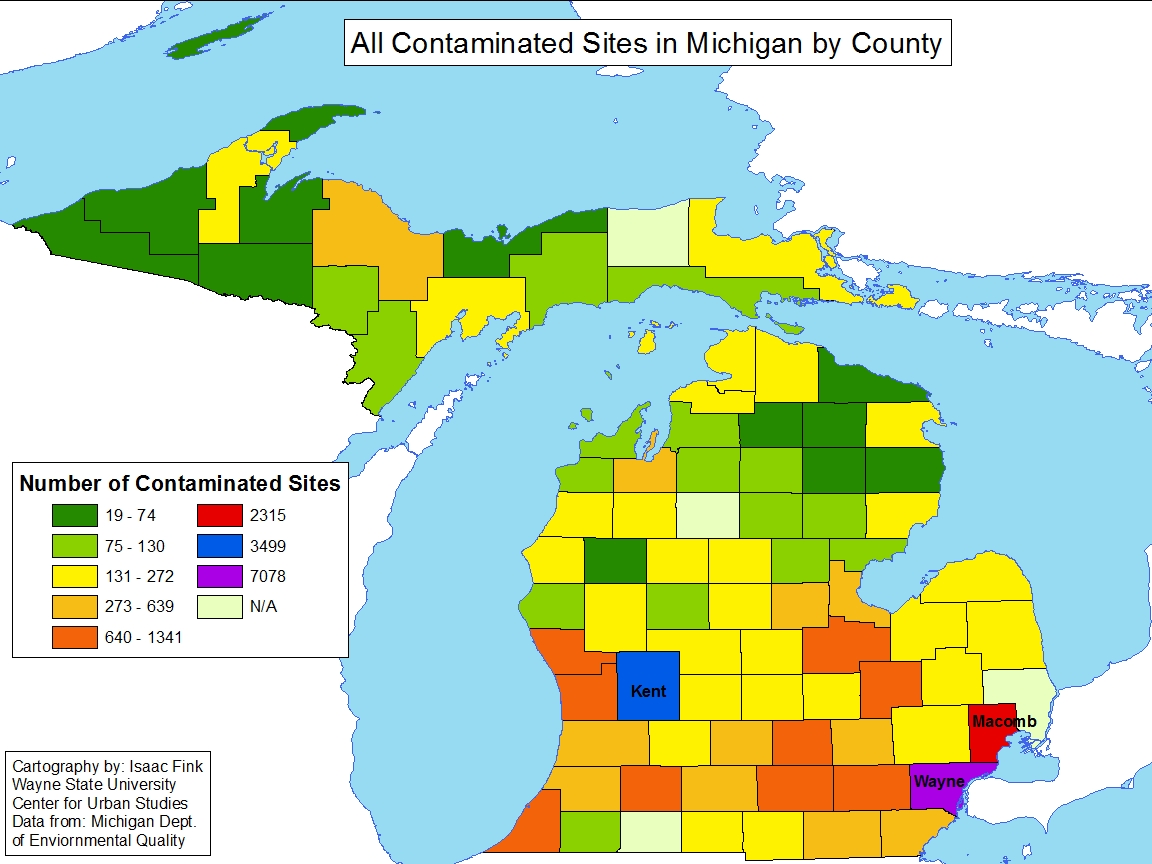

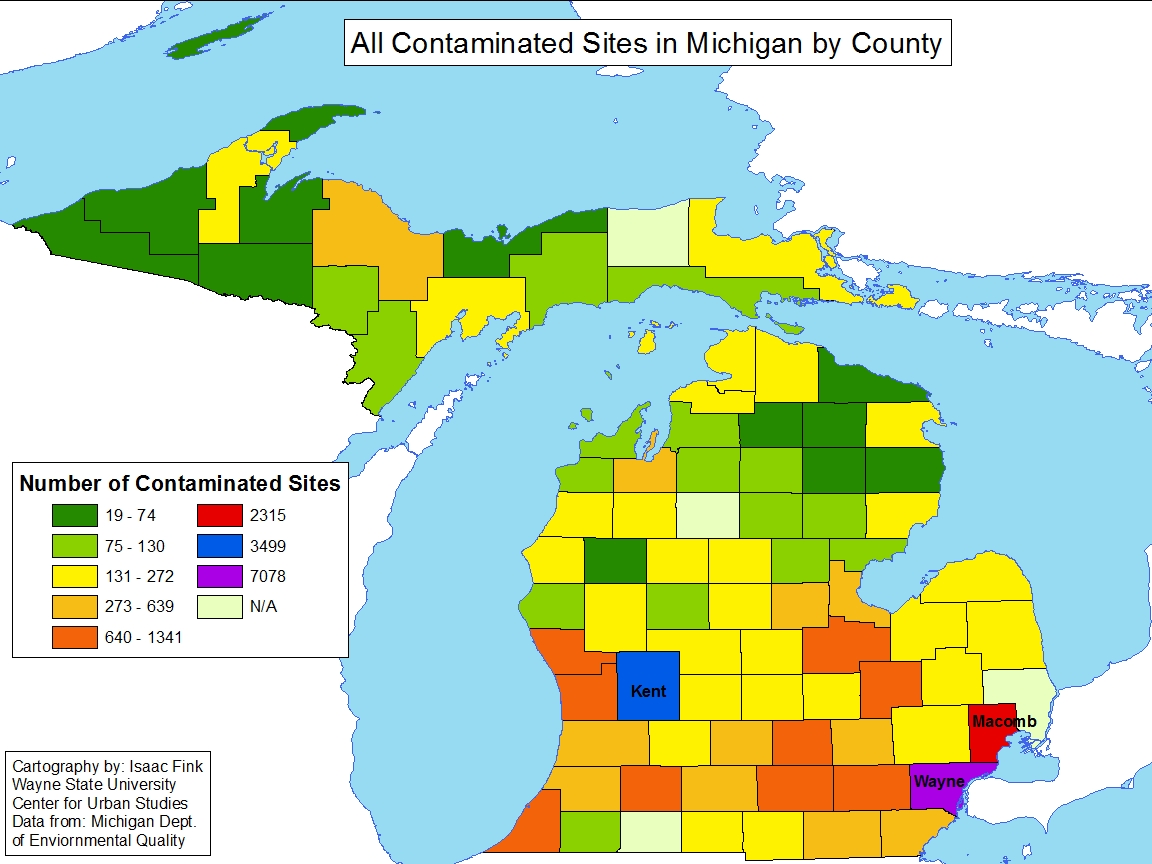

All Contaminated Sites in Michigan by County: BEA, Part 201, Part 213, and Superfund NPL Sites

The map below of the state of Michigan includes BEA, 201, and 213 contaminated sites, as well as Superfund NPL sites. Each color on the map represents the range of BEA, 201, and 213 contaminated sites per county or the actual total. For example, many of the counties with a smaller total number of contaminated sites are designated with a color that is also associated with a range. However, Kent, Macomb and Wayne counties are designated with a color that directly associates to the total number of contaminated sites in that county. The map shows that Wayne County contains the largest number of contaminated sites 7,078 sites. Kent County has 3,499 contaminated sites and Macomb County has 2,315.

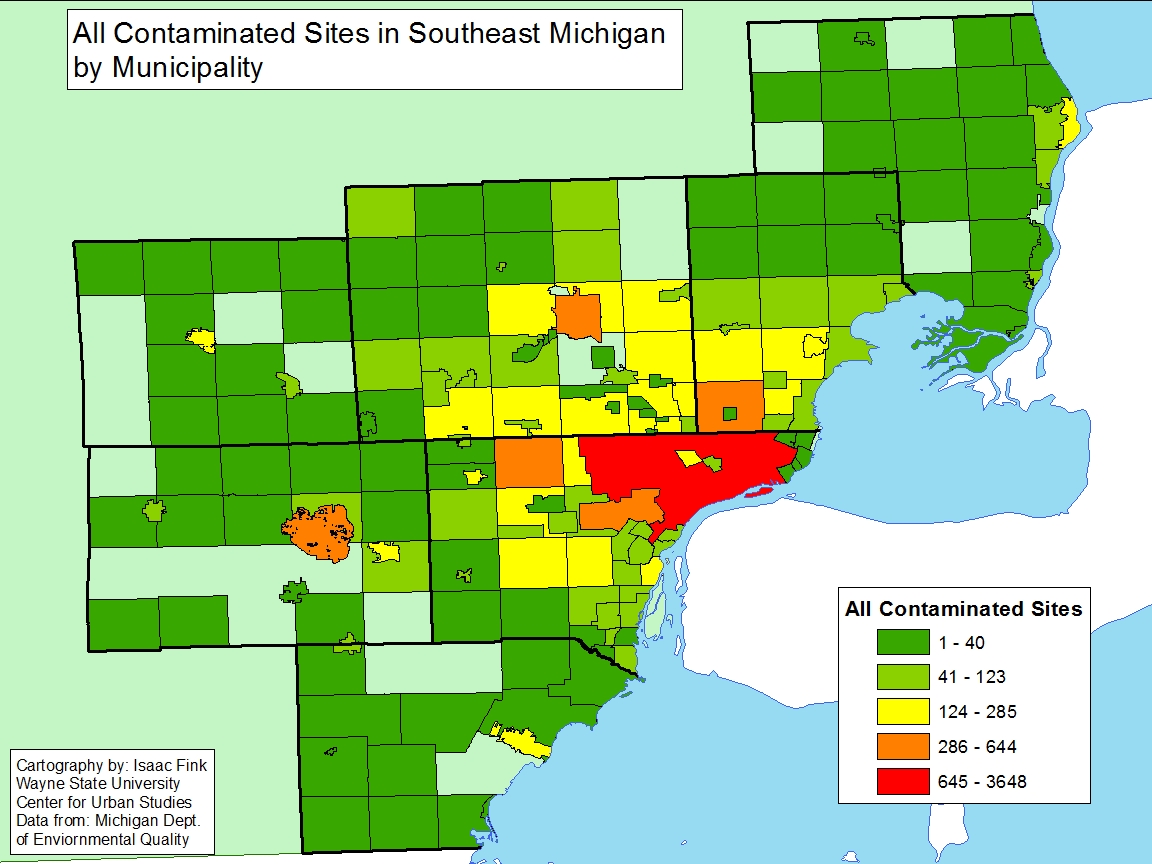

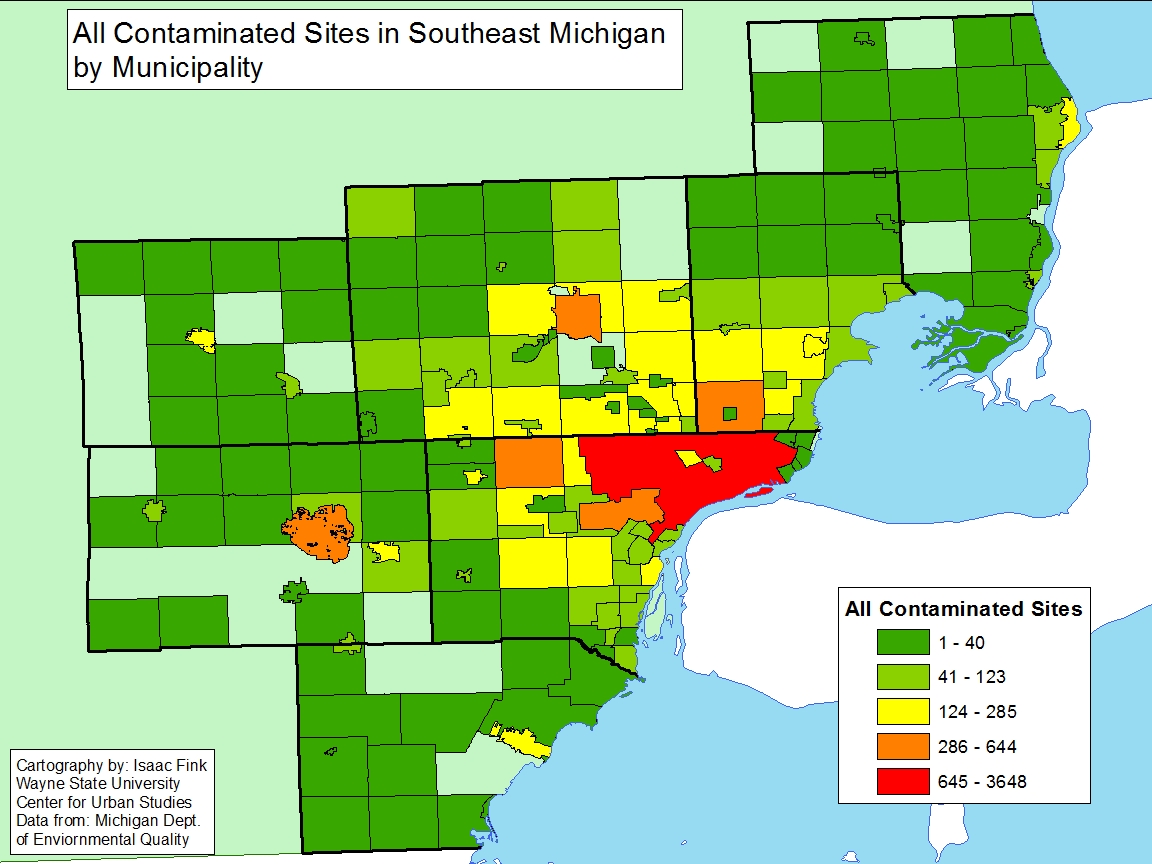

All Contaminated Sites in Wayne County by Municipality: BEA, Part 201, Part 213, and Superfund NPL Sites

The regional map below includes BEA, 201, and 213 contaminated sites, as well as active Superfund NPL contaminated sites and deleted NPL sites. Each color on the map represents the range of BEA, 201, and 213 contaminated sites per city (e.g., Highland Park = 124-285 sites). A green circle indicates a deleted NPL site, while a yellow diamond indicates an active NPL site. The map shows that Detroit contains the greatest number of contaminated sites in Wayne County, with a total of 3,648 (the color red does provide a range, based off the range before it, but Detroit is the only city within the last range). Additionally, there is one deleted NPL Superfund site in Detroit and two in Wayne County. There is also an active NPL Superfund site in Wayne County, in Trenton.

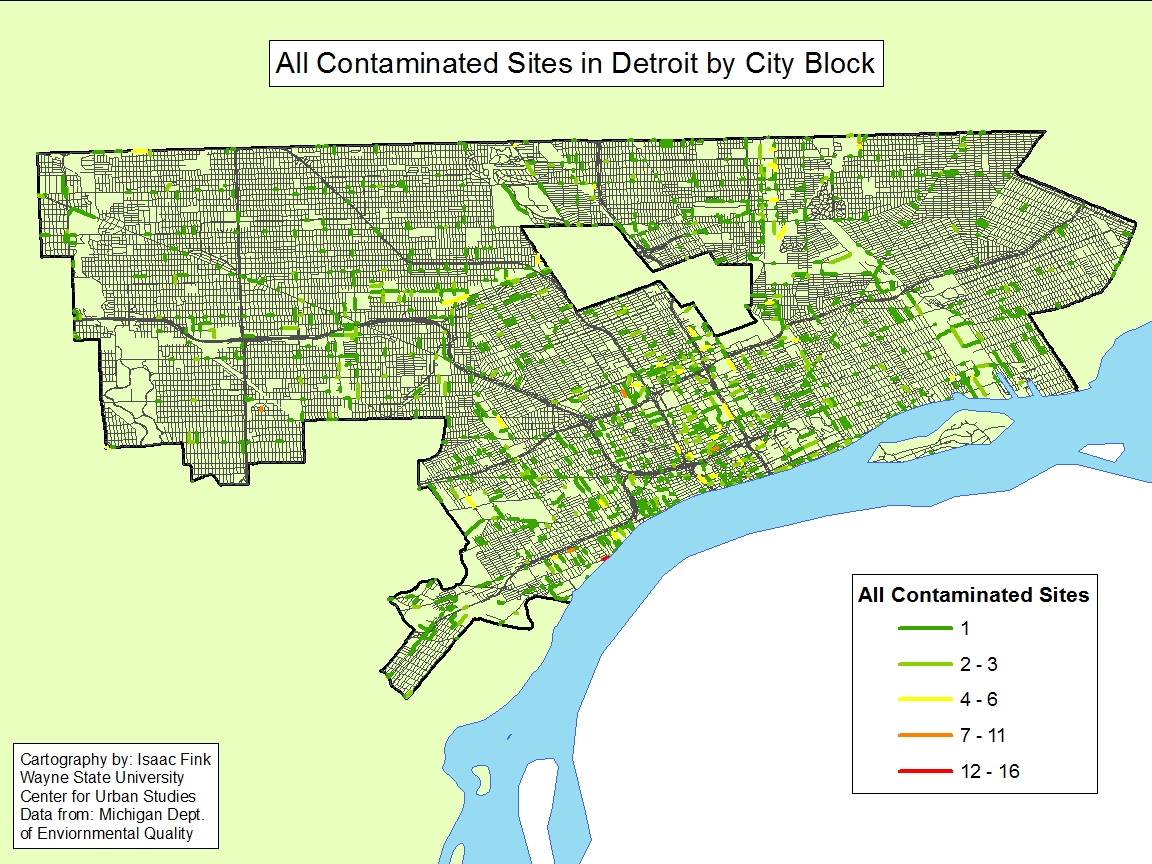

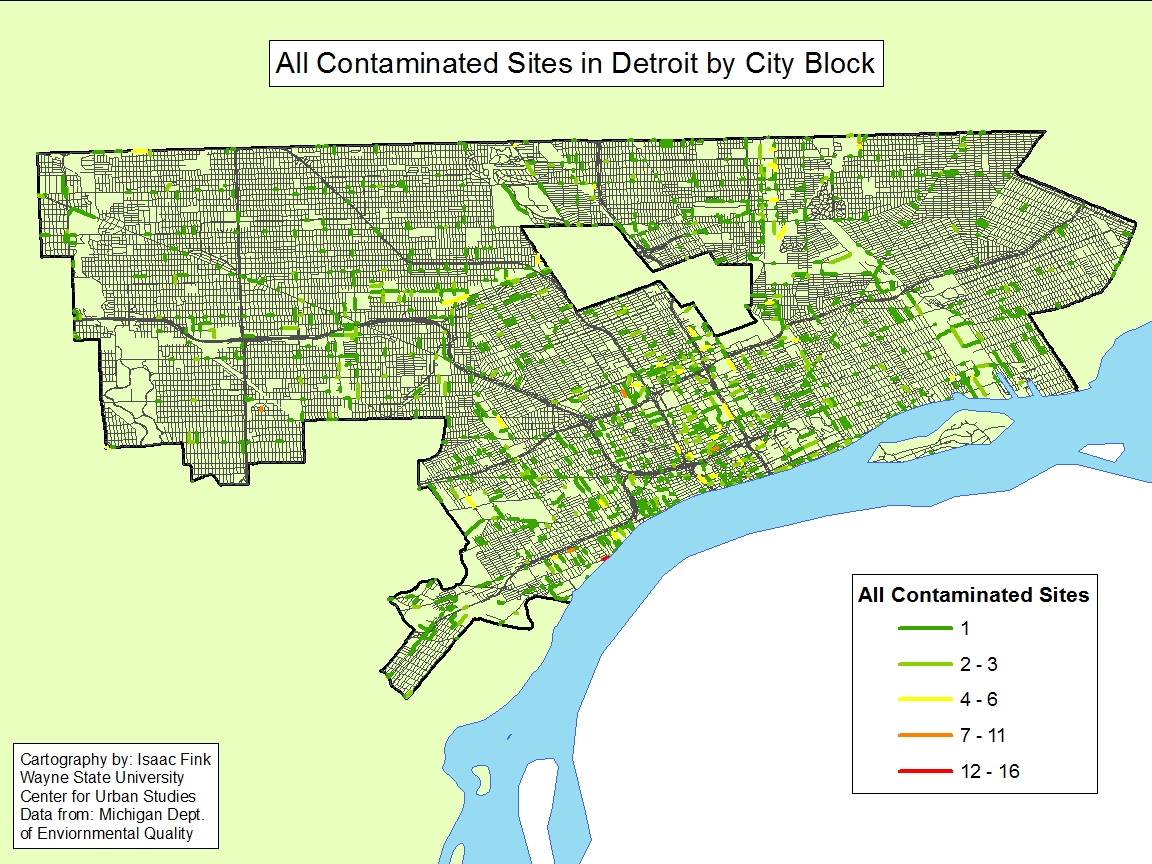

Overall, as the second map below shows, a block in Southwest Detroit has the highest number of concentrated contaminated sites. On a larger scale though, the area just west of Woodward Avenue, south of Highland Park, has several blocks where there are at least one to six contaminated sites.

In this post we simply highlighted the counties and municipalities in the state with the highest number of contaminated sites. However, there is more to this conversation than just that. In a coming post we will also be taking a further dive into where much of these sites are located regionally, specifically Detroit, and the link between income and contaminated sites.