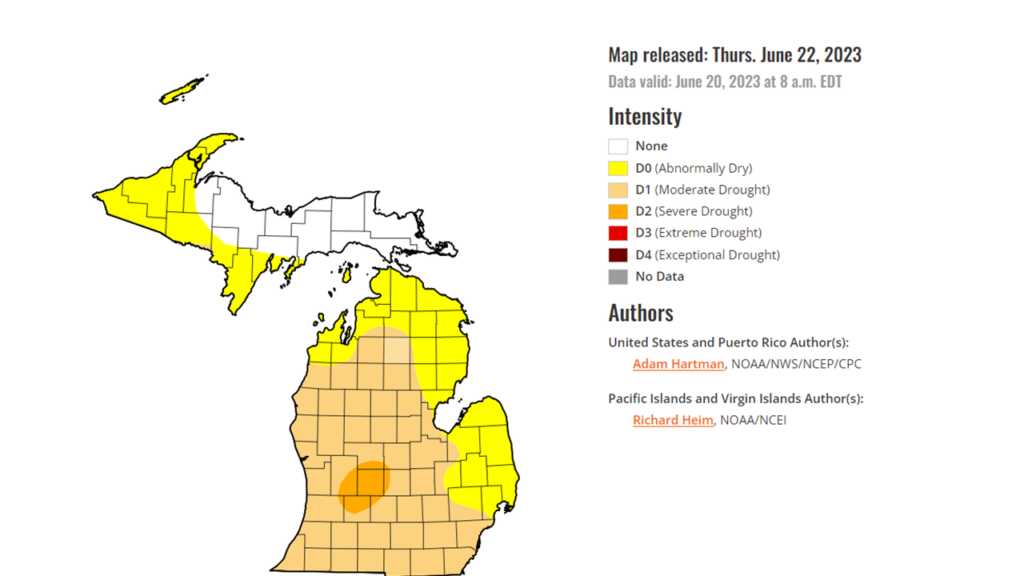

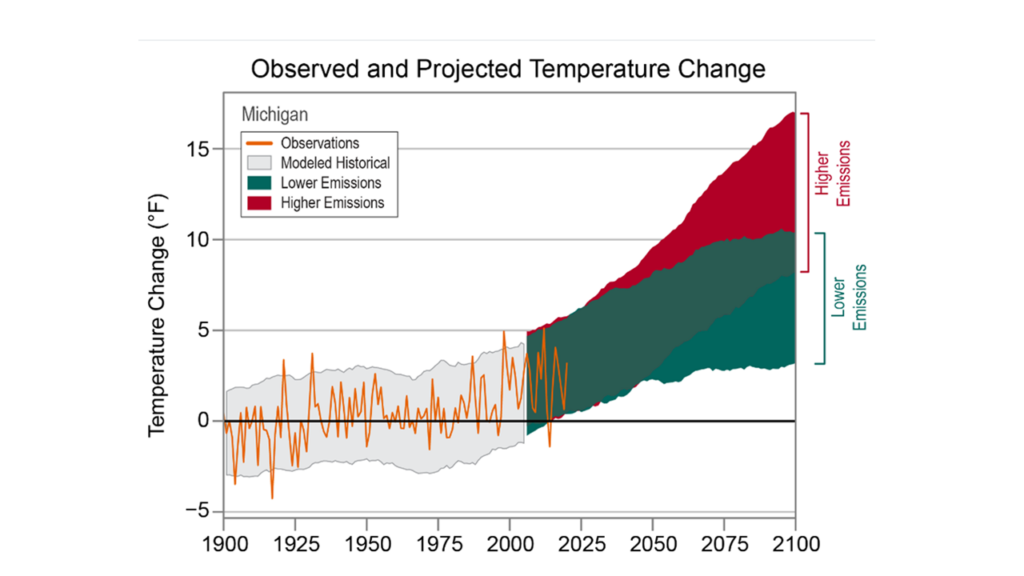

Michigan’s air quality has received a great amount of attention over the last several months. With wildfires still burning and winds bringing smoke into Southeastern Michigan, the region has had more than a dozen Ozone Action days. This increase in Ozone Action days has brought about increased attention to what poor air quality means for our health and what is causing the poor air quality. Smoke caused by increased temperatures and drought has caused wildfires in northern Michigan and Canada; the drought and increased temperatures are direct results of climate change. Climate change is caused by various factors, many of which are related to pollutants.

In this post we will further examine the air quality of Southeast Michigan and some of the factors behind it, particularly some of the region’s biggest polluters.

Of the seven counties in Southeast Michigan, three received an “F” grade for air quality from the American Lung Association in the 2023 State of the Air Report, and the other two that had enough information to be graded did not receive higher than a “C” grade. These grades are based on the number of high ozone days in each county and the change in particle pollution from day-to-day and year-to-year.

Wayne, St. Clair and Macomb counties all received “F” grades for air quality in the 2023 State of the Air Report, with Wayne County have 11 “Orange Days” in 2022, St. Clair County having 10 and Macomb County having 16 “Orange Days.” According to the American Lung Association, when a county has an “Orange Day” that day is deemed “unhealthy for sensitive groups.” Additional colors in this ranking index include red for “unhealthy,” purple for “very unhealthy,” and maroon for “hazardous.” Benzie and Mason counties were the only two in Michigan to have red days.

Furthermore, according the American Lung Society’s State of the Air Report, the Detroit area was ranked the twelfth most polluted for year-round particle pollution.

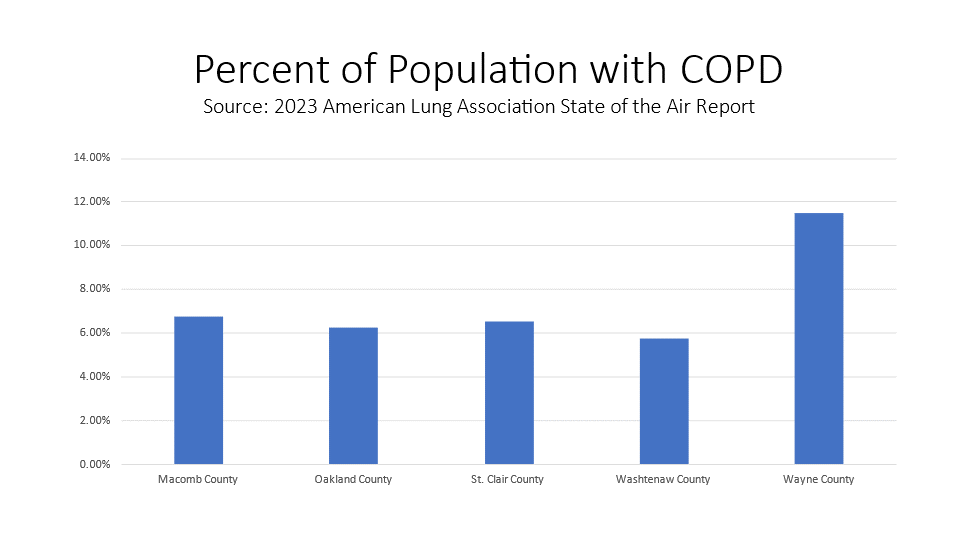

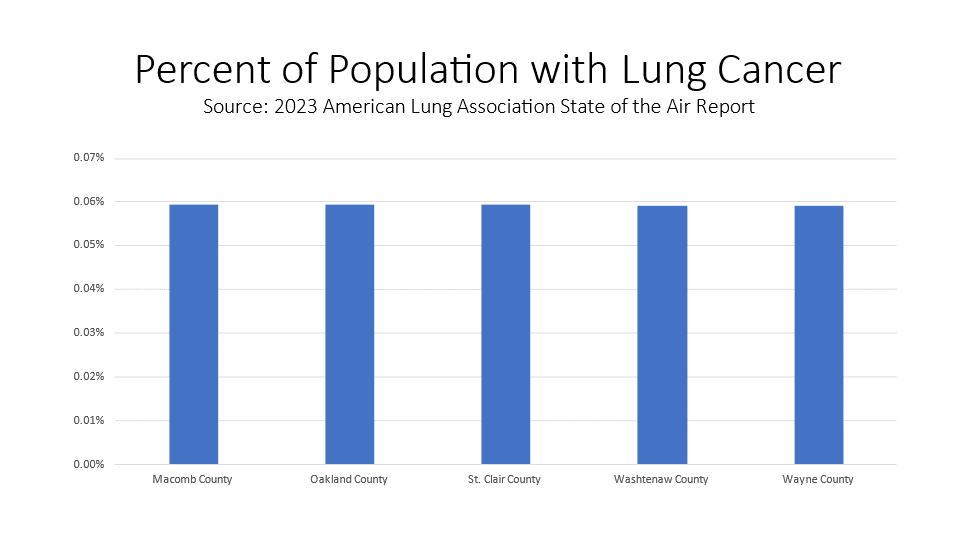

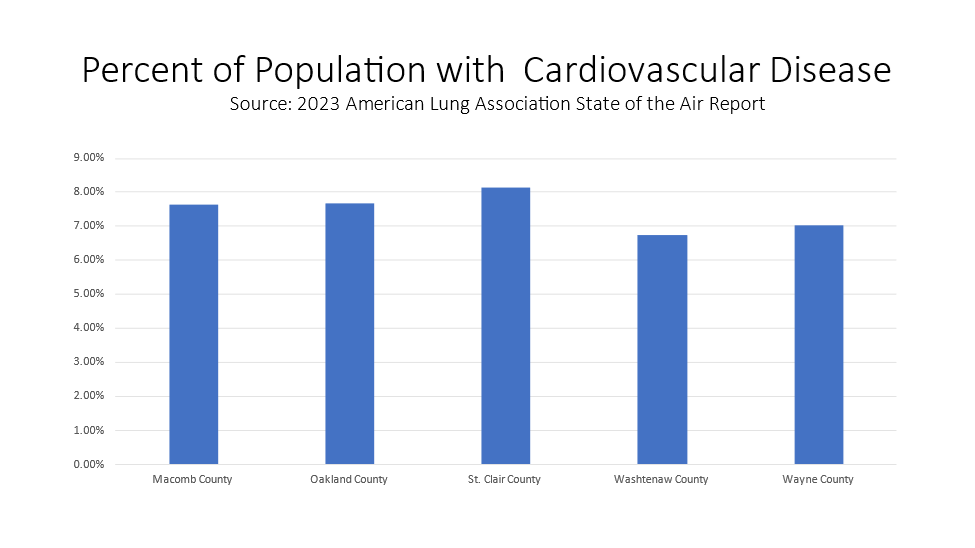

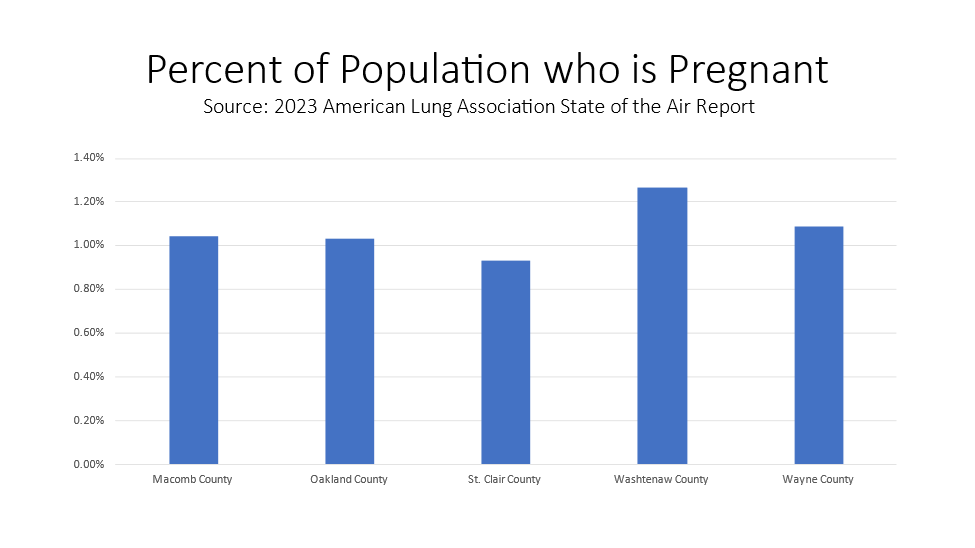

Particle pollution is of serious concern because it negatively impacts individuals’ health, causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems and even premature death. According to the Centers for Disease Control, there are two sources of particle pollution, primary and secondary sources. Primary sources cause particle pollution on their own; wood stoves and forest fires are primary sources. Secondary sources let off gases that can form particles. These sources include power plants, factories, construction sites, vehicles and coal fires.

In Southeast Michigan there are several secondary particle pollution sources that have a negative impact on the area’s air quality. According to climatetrace.org, a global non-profit organization that independently traces greenhouse gas emissions, some of the area’s highest emitters are an oil refinery, two steel plants, an airport and a powerplant. These emitters are:

Marathon Petroleum CO Detroit:

Ranked 378/80,188 Worldwide: for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Cleveland-Cliffs Dearborn Steel Plant

Ranked 296/80,188: for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport

Ranked 917/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Gerdau Monroe Steel Plant

Ranked 1,450/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Monroe Michigan Power Plant (DTE)

Ranked 37/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

These rankings and the acknowledgement of these assets on the Climate Trace map use data from 2021.

Other secondary sources that contribute to particle pollutants in the Metro-Detroit are the highways, the Ambassador Bridge and, most recently, Stellantis manufacturing plants in Warren and Detroit. Over the last several months, Stellantis has been fined over $500,000 for violating emission standards, according to Crains Detroit. Now, instead of trying to cut back on the emissions, Stellantis has submitted applications to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy to raise emission levels of volatile organic compounds and particulate matter at the Warren Plant and to raise the amount of permitted particulate emissions at the Detroit Plant.

It remains unknown what the State of Michigan will do with Stellantis’ requests, but the State and the federal government both need to enforce stricter emission standards, both the benefit of the environment and the population. Higher accountability standards are needed, as are means to produce power and products in ways that do not create greenhouse gases.