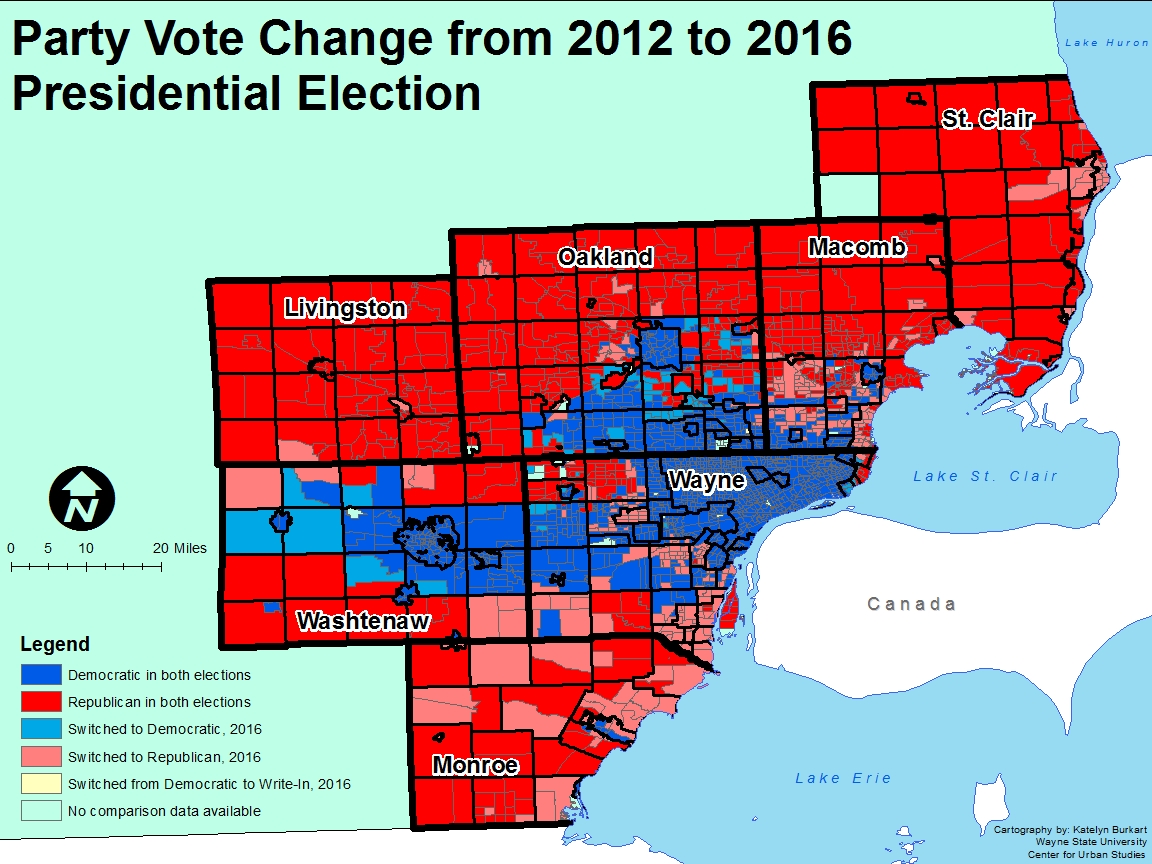

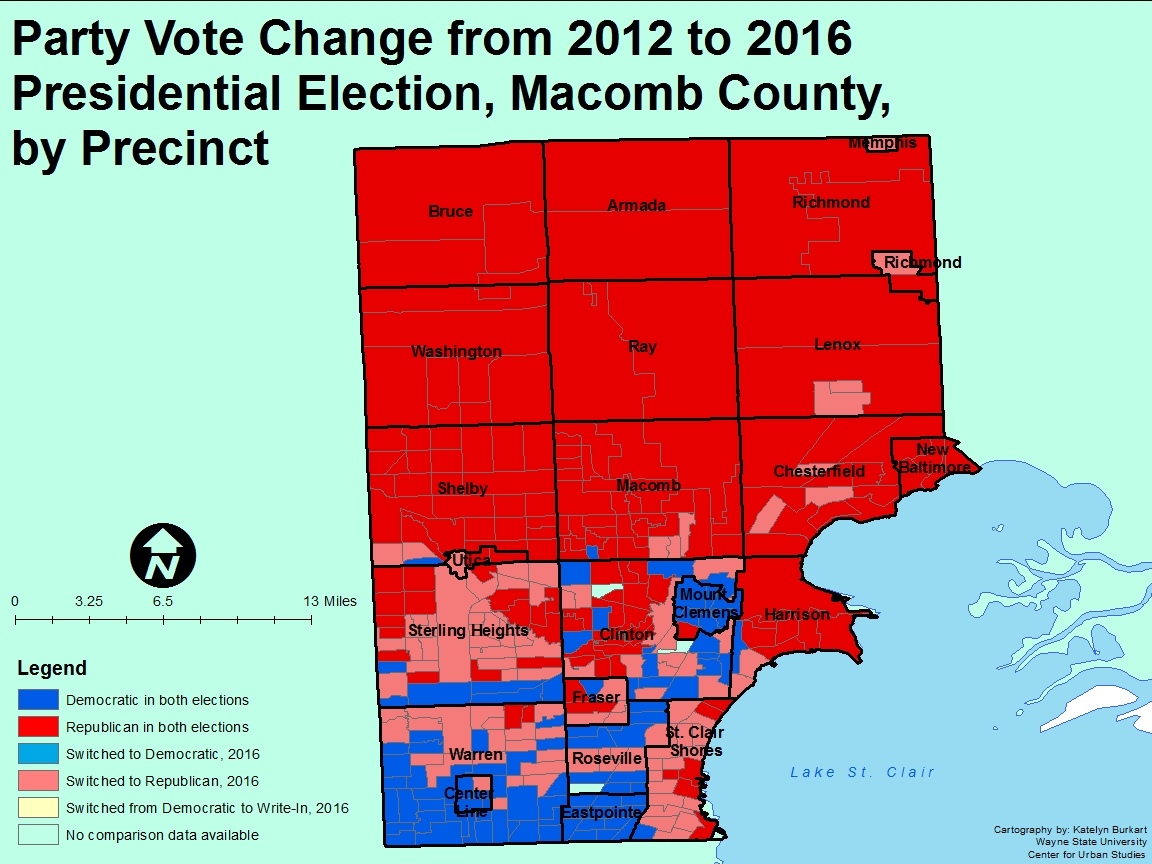

There are two reasons Detroit should have a special place in President-elect Joe Biden’s heart. First, because Detroit needs real help–now. And second is because Detroit is one of the key places that brought his victory. Detroiters voted in massive numbers for him and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, and Democrats will need Detroit voters to win again. As the saying goes, you need to dance with the ones who brung you.

Here, then, are ten agenda items Biden and Harris should prioritize—giving back to a City that helped bring them into office.

1.Make plenty of vaccine doses available. Unemployment linked to COVID-19 closures have hit the poor and those in service jobs far harder than other industries. Unemployment numbers are more than double in Detroit than in Michigan. More vaccines mean it’s safer to go back to work, and Detroiters need that work and the accompanying income now. That will improve many other things mentioned here, including reducing violence.

2. Reduce the violence. We’ve seen major increases in murders and shootings. On surveys through the years, Detroiters have consistently said public safety is at the top of their agenda, but that does not translate to a desire for heavy duty police enforcement across the board. Rather than defund the police, Biden should talk about demilitarizing the police and making them responsive to the true needs of the community. Detroit citizens want tough action against the repeated violent offenders, but they want first time offenders and others diverted out of stigmatizing court process into community service, education and job training programs. For example, police regularly stop hundreds of people and arrest them for carrying illegal weapons. We need to divert these citizens into training programs that teach them about the risks of violence. We need to use conflict deflectors and de-escalators to reduce violence. Increased participation in youth sports and utilization of open community centers will also help deter violence. While many of these outlets have been closed and cancelled due to COVID restrictions, we must find ways to continue to offer such opportunities.

3. Reduce domestic violence. Domestic violence, already high in Detroit, has increased under COVID-19, and the enforcement of parole violations for domestic violence offenders by Michigan Department of Corrections has declined.

Detroit has far fewer shelter beds than surrounding communities for survivors of domestic violence (DV) or intimate partner violence (IPV). This needs to be corrected immediately. Beyond that, survivors need to have far more access to advocates who can help them navigate the complex legal and support systems that do exist. They need more financial help to pay for things like moving to safe locations and serving Personal Protection Orders that are intended to help shield survivors from further violence.

4. Increase jobs for youth. Detroit youth have extraordinary unemployment levels, well above the already high adult unemployment levels. This is a crisis, especially because we know that this will affect their lifetime earnings and connection to the workforce. Such high levels have led to challenges to democracy itself in other times and countries.

We need broad, youth employment programs funded by the federal government and operated by non-profits that do real work to help improve Detroit. These jobs must create job ladders for youth so they have a future in which to invest.

5.Increase support for youth to go to college, apprenticeships, and training at community colleges. Many youth have no real way to pay for college.

We need to increase Pell Grants very substantially so youth who want higher education can get it without having a lifetime of debt, as so many do now. Apprenticeships and training in the skilled trades also often lead to good jobs with benefits and high wages—sometimes higher than college-educated jobs. These opportunities also need more funding so the youth have access to an even wider range of skills and jobs.

6.Fully fund special education. In Michigan, charter schools are implemented in a manner where they generally recruit higher performing students from the public schools, leaving the public schools with fewer higher performing students—who tend to cost less to educate. In major urban areas, charter schools proliferate and the public schools end up with a disproportionate share of special education students, which the charter schools avoid. These students cost more to educate. Because special education is not fully funded by the federal government, the costs are off loaded onto urban school districts in Michigan. These costs drive urban school districts into debt and decline. None of this makes it onto the debate stage, but this is the crucial work that needs to be completed to help Detroit and other cities like it. More federal funding is needed for special education students.

7.Invest massively in home repair. Detroit’s housing is crumbling with 63% of the housing units having at least one major health hazard. Lead paint, lack of heat, flooding, asbestos, Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), structural hazards, fire hazards—these are all present across the range of homes in Detroit both for homeowners and renters.

Detroiters don’t have the money to pay for all these repairs, and Community Development Block Grant dollars continue to decrease. Money for repairs of existing homes is needed to make them safe and to protect existing residents from disease, injuries and break-ins. This will also protect them from gentrification.

8.Protect homeowners from foreclosure. This is a perennial issue in Detroit that turns into a crisis with every recession. In the Great Recession, many thousands of homes were wrenched from homeowners. Now foreclosures are high again.

Short term cash and longer term re-writing of mortgage agreements are critical to short circuiting this endless cycle of foreclosures that has already made Detroit a majority renter city. This too will protect existing homeowners from gentrification.

9.Invest heavily in weatherization. One the highest costs that Detroiters face are their utility bills, both for renters and homeowners. Leaky old houses mean huge heating bills that often take up a large part of the budgets of low and moderate income households. In neighborhoods like Southwest Detroit, where industry and traffic pollute the air, this weatherization should also include air filters to clear the air that people breathe most of the time (Americans typically spend 80% of their time in their homes).

The Obama Administration initiated a large weatherization program but the budget for that got nixed by the GOP in Congress. Now is the time to move forward with this both for the sake of everyday Detroiters and the sake of the planet.

10.Build Community Solar. Unlike many cities, Detroit has lots of open space that could be used for solar energy production. DTE, our local utility, mainly produces electricity from coal, which hurts the planet and the lungs of Detroiters. And, Michigan produces none of this coal. Another way to help Detroiters reduce their utility cost is use some of the massive amount of vacant land in the city for building community solar installations. With investment from the federal government, these could be owned by Community Development Corporations or others who could sell the solar power at cost to homeowners nearby. Investing in these small-scale production facilities would produce installer jobs for Detroiters, increase reliance on alternative sources of electricity, cut costs for citizens and make appropriate use of vacant land.