Regionalism in Southeastern Michigan began to take shape in the 1930s, but it was not until the financial decline of Detroit and the broader region, that multi-jurisdictional authorities truly began to take over an array of services.

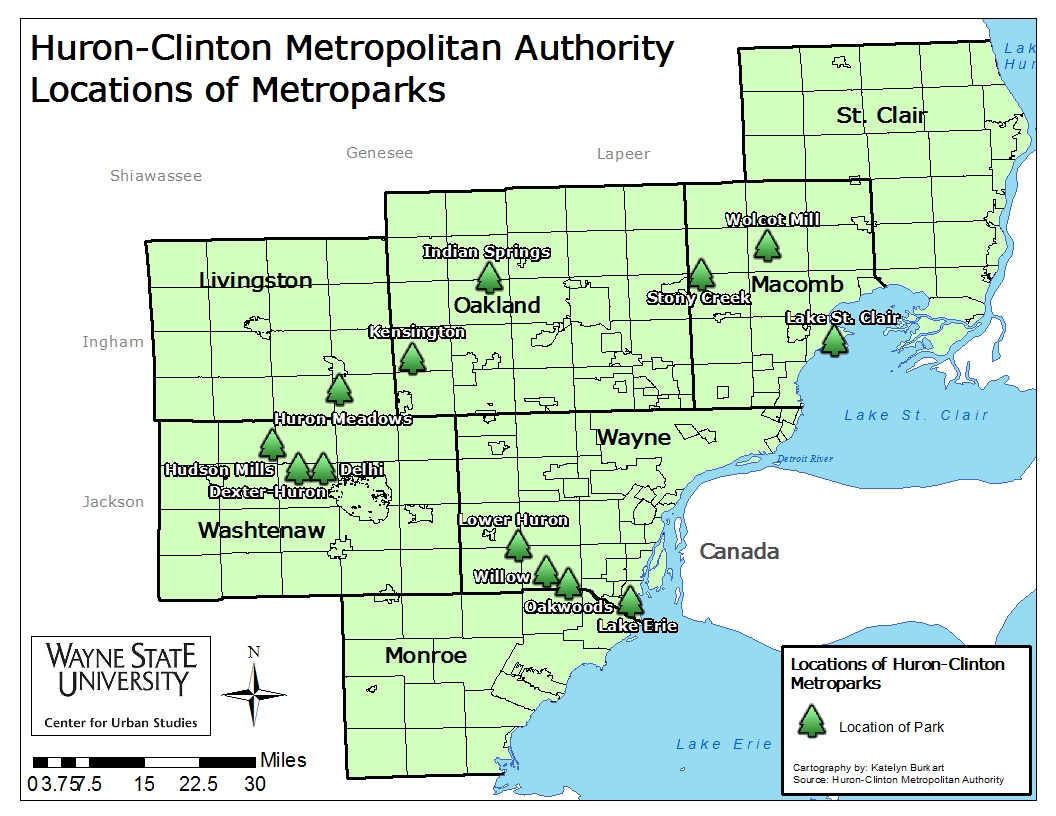

The oldest extant regional entity formed in Southeastern Michigan is the Huron-Clinton Metropolitan Authority. Enabled by the Michigan State Legislature in 1939 by Public Act No. 147, the residents of Livingston, Macomb, Oakland, Wayne and Washtenaw counties approved the authority the following year. In 1942, funding for the parks became available, according to the authority’s history. Since that time the authority has grown to oversee 13 metroparks, which together encompass more than 25,000 acres. The Huron-Clinton Metropolitan Authority is governed by a seven-member board; two members are appointed by the governor and the other five are appointed by the Board of Commissioners of the member counties. Currently, all of the metroparks are supported by a 0.2146 mill levy on the residents of Livingston, Macomb, Oakland, Wayne and Washtenaw counties. This levy is equivalent to $10.73 for a home valued at $100,000 ($50,000 taxable value).

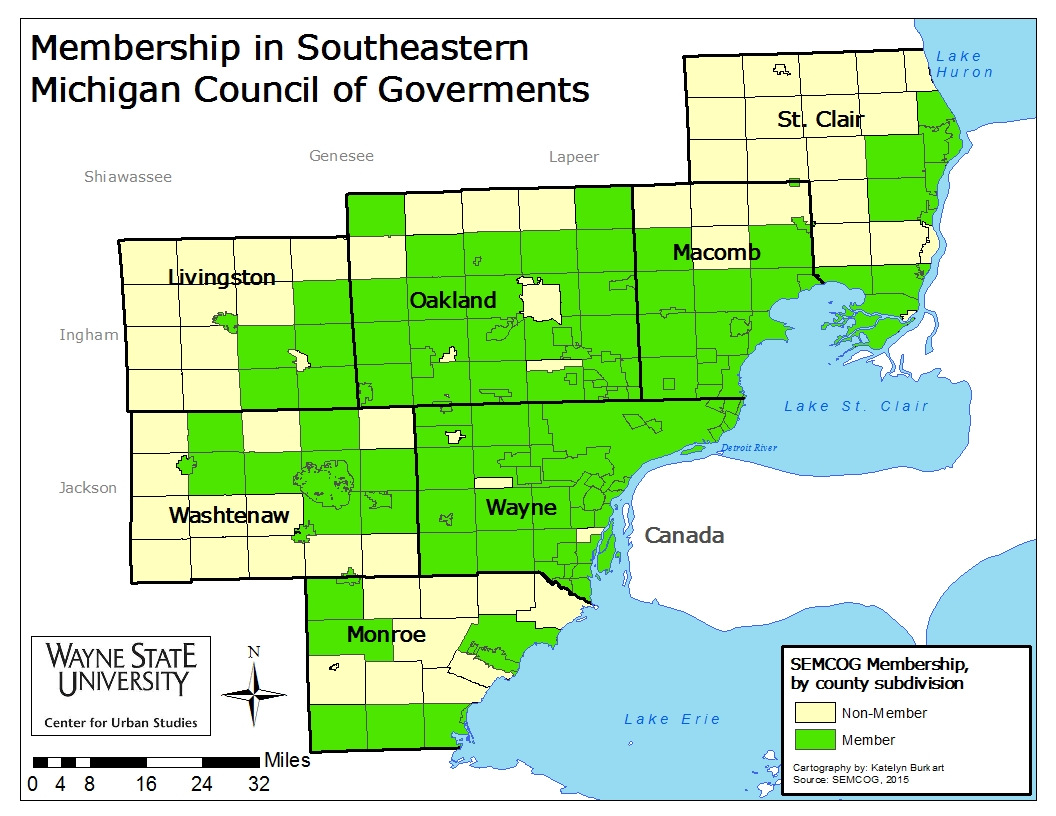

Southeast Michigan took an additional step toward regional cooperation more than 25 years later (1968) by establishing the Southeastern Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG). This regional planning entity, along with other regional planning organizations in the state of Michigan, was authorized by Public Act 281 of 1945.

According to its website, SEMCOG partners with local government entities—ranging from villages to cities to counties to community colleges—to better improve the area’s waterways, transportation systems and economic vitality. In addition, according to the Clean Air Act and the Water Pollution Control Act, SEMCOG is the region’s planning agency for water and air quality. SEMCOG has also been responsible for the region’s transportation planning.

For SEMCOG, communities choose whether or not they want to be members of regional planning entity. As of the end of 2015 there were 168 different government entities that were SEMCOG members. In Macomb County, Ray Township, along with the townships of Armada, Bruce and Richmond are not SEMCOG members despite their neighbors like Washington and Macomb townships being members. In Oakland County, Pontiac is not a SEMCOG member despite it being surrounded by members.

Despite the existence of regional entities, cooperation among cities and counties in Southeastern Michigan was very limited during much of the 20th century. But Michigan’s economic downturn in the 2000s weakened some of the region’s strongest institutions as they began to face financial problems. One of the first organizations to seek public support through a regional millage was the Detroit Zoo. Once completely owned and operated by the city of Detroit, zoo operations were transferred to the Detroit Zoological Society in 2006. This decision came after the city voted to close it for financial reasons, and the Michigan Legislature promised to provide $4 million to the society for operational aid, according to a 2005 Crain’s Detroit article. Then in 2008, the Michigan Legislature approved Public Act 49, allowing counties to establish a zoological authority and contract for zoological services. The act also gives the counties the authority to levy up to 0.1 mill, with voter approval, for such services. In the same year Public Act 49 was passed (2008), the voters of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties were asked to approve a 10-year 0.1 millage, which equals to $5 a year for a home valued at $100,000 (taxable value of $50,000). All three counties approved the millages:

- Wayne County: 73.15% yes

- Oakland County: 74.88% yes

- Macomb County: 66.5% yes

Each of the three counties has its own zoo authority, whose members are appointed by their county commissions or by the county executive office. In Oakland County, the board of commissioners appoints the members; in Macomb County the County Executive makes the appointment recommendation but the Board of Commissioners must confirm; and in Wayne County the executive makes the appointment. Each authority is charged with administering the funds levied from the millage to the Detroit Zoo.

The successful 2008 request for financial support was not the first time the Detroit Zoo sought public assistance through tax dollars, though. In 2000 and 2002 millages were placed on the ballot; Wayne County supported those requests and Oakland County did not, causing them to fail. Macomb County did not participate.

The 2008 millage, which was passed to support operations at the zoo, contributed to 36 percent of the organization’s operational budget in 2014, according to its 2014 financial report. The breakdown of the percentage of millage funds provided to the zoo from each county in 2014 were as follows:

- Wayne County: 13%

- Oakland County: 16%

- Macomb County: 8%

- (64% funds earned revenue and through fundraising)

Following the regional support for The Detroit Zoo another regional authority was created—this one intended to support Detroit’s Cobo Hall. In September of 2009 the Detroit Regional Convention Facility Authority was formed through passage of Public Act 554 in 2008, which allowed the creation of regional convention facility authorities. This regional authority was formed at a time when the North American International Auto Show threatened to abandon Cobo Hall and Southeast Michigan due to the facility’s size and aging infrastructure, according to a New York Times article. Detroit could no longer financially maintain the convention center at a level that would allow it to host such an international attraction.

When the Detroit Regional Convention Facility Authority was formed, so was a governing body to oversee the regional authority. The governing body is a five-member board with representatives from the City of Detroit, Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties and an appointee from the Governor’s Office. This body oversees the 30-year capital lease of Cobo Hall (the facility is leased from Detroit), which includes a $299 million expansion/upgrade project. The Detroit Regional Convention Facility Authority receives funding from revenues at Cobo Center as well as support from the state’s Convention Fund.

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) authorities (one each in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb) were also created during the 2008 economic downturn to help establish a more reliable base for operations funding for the Detroit Institute of Art. Public Act 296 of 2010 gave each of the three counties the ability to levy up to $10 for a home valued at $100,000 (taxable value of $50,000), with the support of voters, to support “an encyclopedic [comprehensive] art museum whose primary art collection and facility. . . are owned by a municipality located in the state.” Similar to the Detroit Zoo authorities, each county board and/or executive appoints members to its respective authority to oversee the funds brought in through the millage.

In November of 2012 majority of Wayne County (67%), Oakland County (64%) and Macomb County (50.5%) approved the 10-year, 0.2 mill proposal that allows free general admission to residents of the tri-county area. Other benefits of the now-established regional authority include free bussing for school field-trips and senior citizen trips, along with the Inside-Out Program, which brings reproduced pieces of art to area communities.

The approval of the millage meant increased funding for the DIA, along with increased attendance. In 2014, according to the DIA’s Community Relations Report, the institute has about 300,000 total visitors from the tri-county area. The breakdown is as follows:

- Wayne County: 141,659 = 47% of total visitors

- Oakland County: 106,433 = 36%

- Macomb County: 51,834 = 17%

While the DIA millage may still seem to receive the most attention, with concerns over raises and transparency, it certainly was not the end of Southeastern Michigan’s increased shift toward regionalism. Over the next two weeks we will also explore the region’s history of fragmented regional transportation and shift from the region’s reliance on Detroit for water and sewer services to a more collaborative approach.