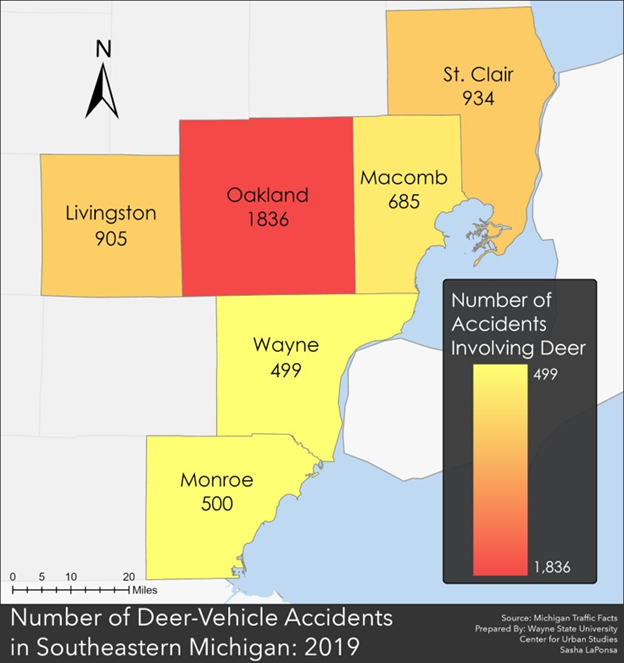

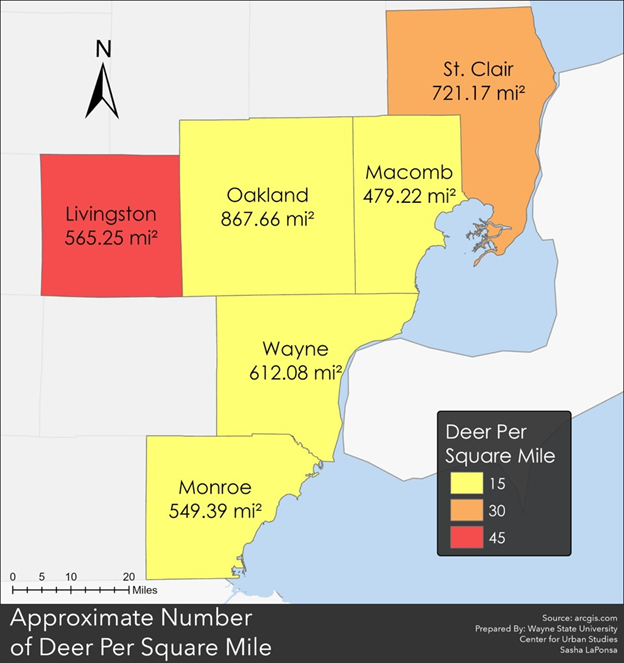

There are about 2 million deer in the State of Michigan and they are most active in the spring and fall at dusk and dawn. Such activity, especially in areas more heavily populated by deer and vehicles, can be attributed to thousands of deer-vehicle crashes a year. According to Michigan Traffic Facts, in Southeastern Michigan in 2019 Oakland County had the highest number of deer-vehicle crashes at 1,836. It is estimated by data3 from ArcGIS that Oakland County has a deer population of about 13,000, or 15 deer per square mile. Regionally, Livingston County has the highest deer population at about 25,400, or 45 deer per square mile. According to the data, there were 905 deer-vehicle crashes in Livingston County in 2019. Wayne County reported the fewest number of crashes in 2019 at 499; Wayne County’s deer population is estimated to be about 9,200 per square mile.

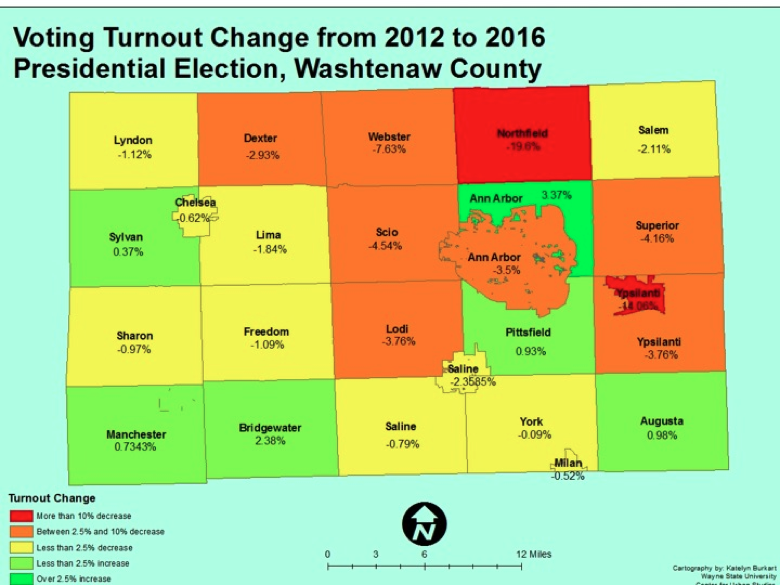

Washtenaw County data is forth coming.

While the size of a deer population plays a role in the number of deer-vehicle crashes in a county, so does the amount of traffic and how their living environment has been impacted. The Average Annual Daily Traffic map from the Southeastern Michigan Council of Governments shows that Livingston County has far less daily traffic than Oakland County. So, while Livingston County may have a higher deer population than Oakland County, the amount of traffic clearly plays a role. Also, according to the Michigan State Police, 80 percent of deer-vehicle crashes occur on two-lane roads.

As areas further develop, deer and humans are also interacting more, particularly as deer become more comfortable with their new neighbors. Backyard gardens, bird feeders and other items the deer prefer to munch on also bring them more in contact with humans, and the areas they live in—including their roadways–as they look for easily accessible areas to eat.

Deer-vehicle crashes may not be entirely avoidable but there are solutions to at least curb them. Such ways to avoid crashes with a deer include:

- Watching the sides of the road as you drive, particularly in low visibility or tall grasses and woods near the road;

- Being aware for groups of deer. If one deer crosses the road there is a good chance more may cross as they tend to travel in groups;

- Using high beams at night (when possible) to help see farther ahead and to identify the eye-shine of a deer;

- Avoiding swerving around a deer, instead break firmly and honk the horn;

- Slowing down.

Government entities can also help curb the amount of deer-vehicle crashes by:

- Enforcing speed limits;

- Installing fences 8 feet or higher in high deer traffic areas to keep them off the road;

- Studies to identify frequently used pathways of deer and setting up warning signs for drivers.

- Installing specific devices that warn deer of oncoming traffic to scare them away from the road.