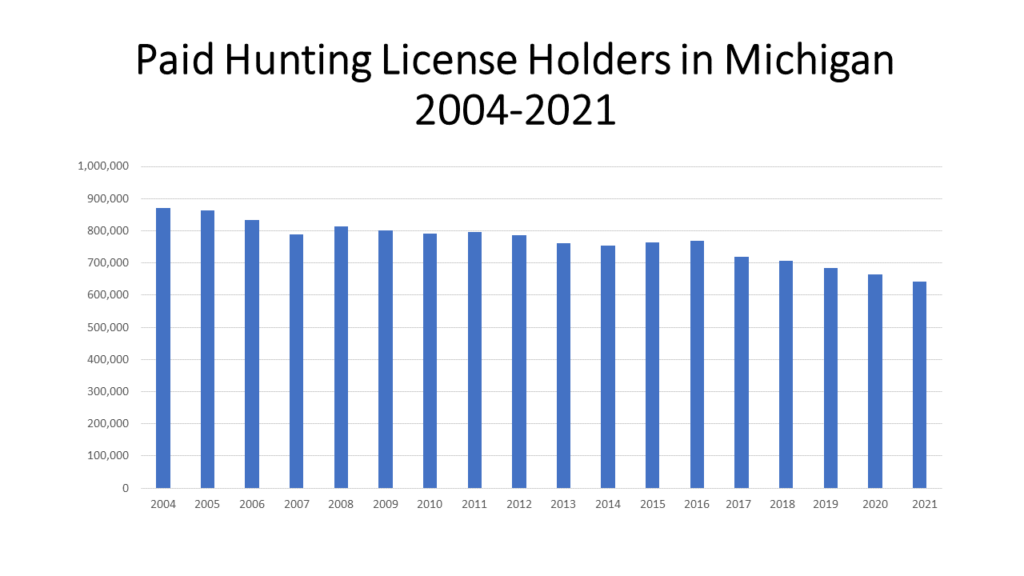

Hunting in Michigan isn’t what it once was, at least according to the data. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service the total number of paid hunting license holders in Michigan has been on the decline for well over 15 years. In 2004 there were 870,432 paid hunting licenses in Michigan and by 2021 that number declined to 642,242 licenses. These numbers are reflective of all the hunting licenses in the State of Michigan, including those purchased by non-residents of the State. In addition to needing a hunting license to hunt in the State of Michigan tags, permits and other regulatory forms are also needed to hunt certain animals in Michigan; those numbers have been declining as well.

According to a recent article by Bridge Magazine, a large reason for the decline of nearly 230,000 hunters in Michigan is because of a shift in interest. The article quotes Dustin Isenhoff, a Michigan Department of Natural Resources research specialist who tracks hunting participation, who says that many of the State’s avid hunters are aging out of the sport, and many of today’s children don’t have the same interest in the sport.

With the decline of participation in hunting also comes the fear of a decline in revenue. Twenty percent of the Michigan Department of Natural Resource’s revenue comes from fees from hunting and fishing licenses. In 2014 then Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder increased the cost of hunting licenses to increase revenue from an already declining sport. In some cases, the cost of a license doubled; a typical deer license once cost a Michigan resident $15, it increased $31. And, while that has brought on increased revenue there is still the fact the number of licenses being sold is dropping significantly.

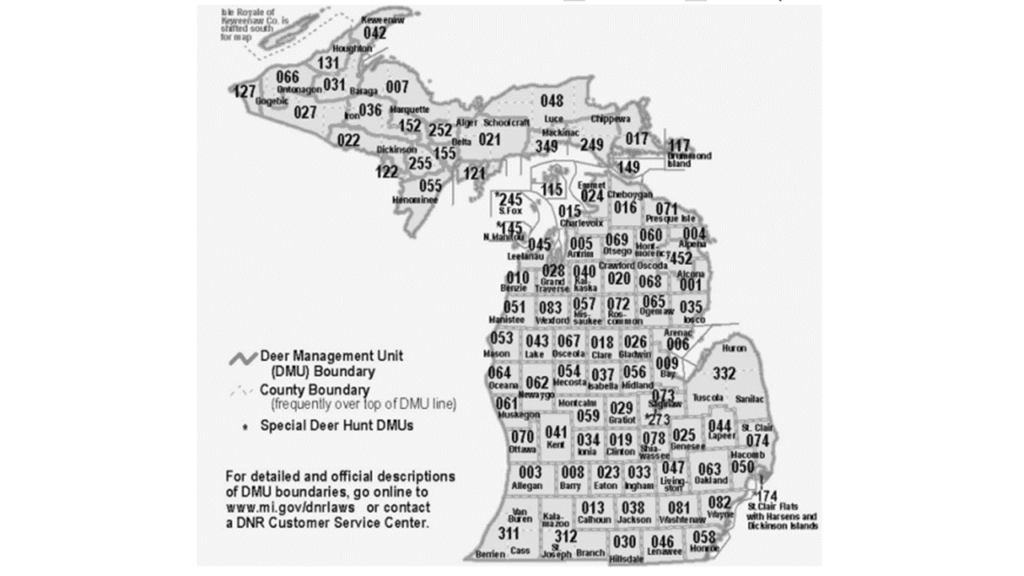

The map below shows the number of deer harvested in each county in Michigan in 2020; these numbers do not include the 9,557 that were taken with deer management permits though (these are specifically used for population control). One notable area with a high number of harvested deer and several designated hunting areas is Van Buren, Berrien and Cass counties in Southwestern Michigan. However, even with all the number of deer harvested combined in the map below, the total number is less than the number of deer harvested for population management, which is also a controversial topic.

Hunting only does so much to control the deer population as it is seasonal and can only take place on designated lands. There are deer culling programs in places like Grosse Ile and Meridian Township, but, as alluded to earlier, these programs often draw strong opposition. An Ann Arbor program was cancelled after years of opposition from residents.

Some consider deer as a nuisance to gardeners and that they drive out certain species due to their overpopulation and often are a hazard to drivers in certain places. Others note that the natural predators to deer, including coyotes and cougars, were eliminated in most places in Michigan, although the coyote population is now rising.

The issue of deer hunting and population control is one that is complex and requires a delicate balance. Some call to open more public hunting land in Southeastern Michigan to allow for easier access to the sport and to better control the deer population where numbers are growing due to less space for them to live. However, the risks to hikers, cyclists and other users of open space is significant as well.

Between 2010 and 2018, 16 deaths and 86 non-fatal injuries were linked to hunters’ weapons, according to Michigan Department of Natural Resources reports analyzed by Bridge. In 2015 and 2016 there were not any hunter deaths reported; these were the only two years, at least since 1970, when that happened.