In the state of Michigan, 13.3 percent, or about 206,000 students, were considered to be Special Education students for the 2014-2015 school year. Many urban and rural districts had a higher percentage of special education students than their suburban counterparts in Southeastern Michigan. However, according to a 2014 Bridge article, special education designations vary from district-to-district; it comes down to a very local decision.

According to the state of Michigan there are 13 disability types that may cause a student to be considered a special education. These disability types are:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Cognitive Impairment

- Deaf-Blindness

- Early Childhood Development Delay

- Emotional Impairment

- Hearing Impairment

- Physical Impairment

- Severe Multiple Impairment

- Specific Learning Disability

- Speech and Language Impairment

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Visual Impairment

- Other Health Impairments

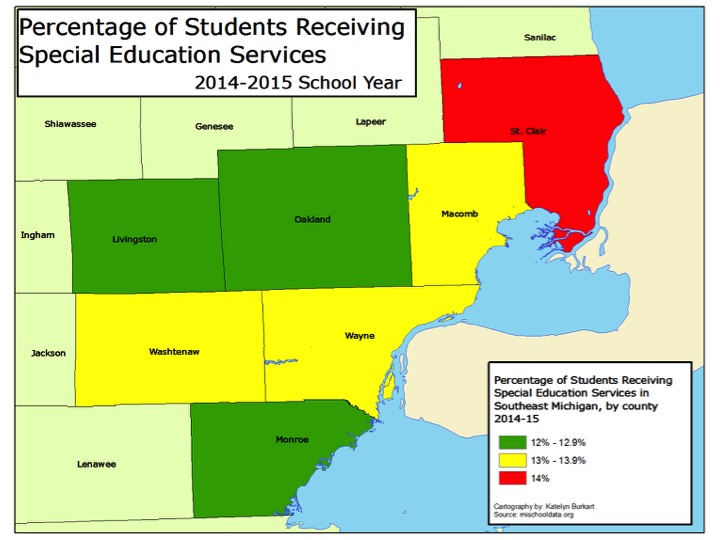

At the county level (which is represented by data provided for the county intermediate school district or regional education service agencies), the St. Clair County Regional Education Agency had the highest percentage of special education students at 14 percent and the Livingston Education Service Agency had the lowest at 12 percent.

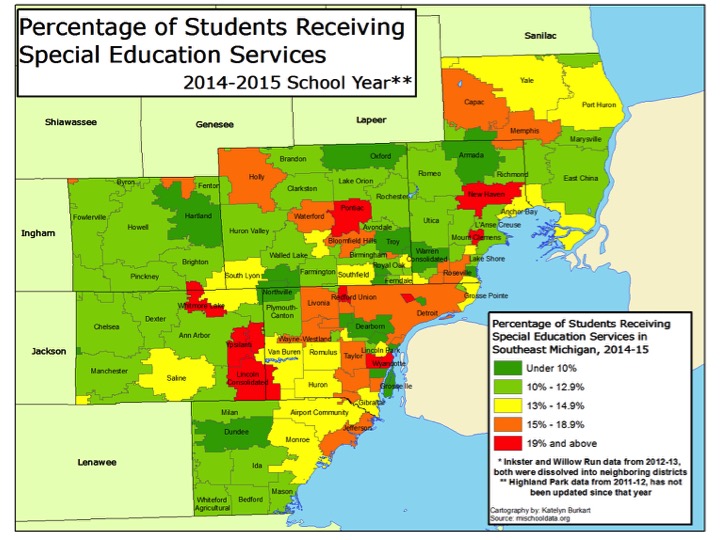

Of the 100 public school districts in Southeastern Michigan, Mount Clemens School District had the highest percentage of special education students during the 2014-2015 school year at 26.5%. In Macomb County, 36 percent of the school districts had a higher percentage of special education students than the state average of 13.3 percent. Macomb and Oakland counties each had eight school districts with a percentage of special education students that was higher than the state average. It was St. Clair County though that had the highest percentage of public school districts with a higher percentage of special education students over the state average. Of the seven public school districts in St. Clair County four had more than 13.3 percent of its student body designated as special education. Capac Community Schools had the highest percentage in the county at 17 percent.

In Wayne County, the Wyandotte School District had the highest percentage of special education students at 24.7 percent. The Detroit Public Schools had 18.2 percent of its student body categorized as special needs during the 2014-2015. The Wayne County public school districts that had a higher percentage of special education students than the Detroit Public Schools were:

- Garden City Public Schools (18.8%)

- Redford Union Schools (19.9%)

- Southgate Community School District (18.9%)

Below are the public school districts in each county, not already discussed, with the highest percentage of special education students

- Monroe County- Jefferson Public Schools (15%)

- Oakland County- Pontiac Public Schools (19.2%)

- Washtenaw County- Whitmore Lake Public School District (21.1%)

While special education designations remain a local decision, Michigan Lt. Gov. Brian Calley recently called for special education reform, including “breaking down the walls between general education and special education” and creating a multi-tied system of support that is centered around the philosophy that each student is unique. Calley said he doesn’t want a child’s education to be tied to their diagnosis, but rather their specific needs. For more on this click here.