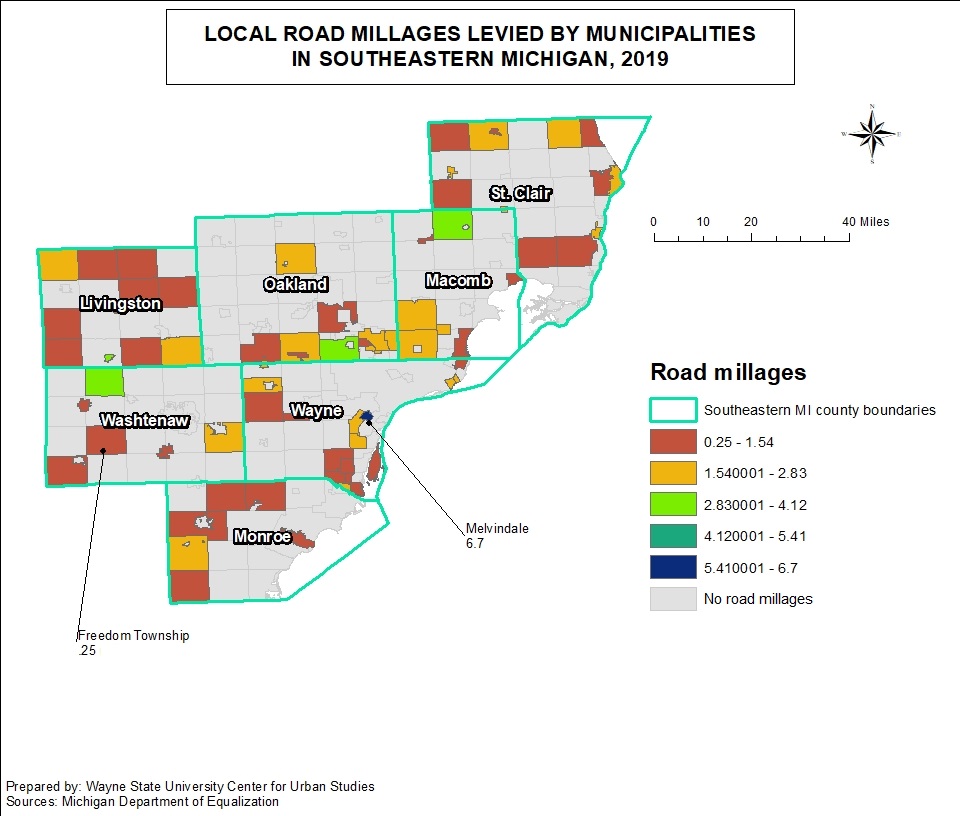

The Regional Transit Authority, which is charged with coordinating regional services and developing rapid transit along Woodward, Gratiot and Michigan Avenue corridors in Macomb, Oakland, Washtenaw and Wayne counties, placed a millage on the ballot in 2016 to support such operations. That millage failed and while the sentiment for public transportation in the region has seemed to increase, we are now left wondering whether it is simply public transportation that has garnered more support, or if it is regional transportation.

Millages supporting SMART (the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation) passed in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties in the November 2022 election. Since 1995 each of the three counties have passed such millages every four years to support this local transit authority, although in 2022 the margins for approval of these millages was higher only higher for Macomb County as compared to the approval rates in 2018. None the less, the millages were approved in all three counties, again, such consistency is about to change—whether it’s for the long-term better or worse remains unknown though.

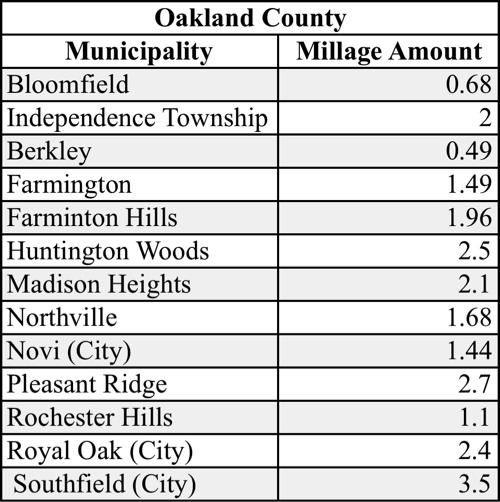

For the short-term, the millage renewals will continue to support public transportation throughout Wayne, Macomb and Oakland counties, and will allow for services to be expanded. Oakland County is the key example of where services will be expanded. Once an “opt-out” county, where each municipality could decide if it wanted to leverage tax dollars to support the public transportation service, Oakland County is now a fully opt-in community. Along with ballot language that gave way to Oakland County being an opt-in county, the now approved millage language also gave way to a 10-year countywide transit millage that will levy 0.95 mills a year starting in 2023. For a home valued at $200,000 (or a home with an SEV of $100,000) the homeowner will pay $95 a year to support the newly approved SMART millage. The Oakland Transit Millage will not only support SMART but also the North Oakland Transportation Authority (NOTA), the Western Oakland Transportation Authority (WOTA) and the Older Persons Commission (OPC) in the Rochester area.

According to Oakland County, these funds levied through the approve transit millage will support services that specifically benefit Oakland County residents and businesses. With the approved millage, Oakland County transit is expected to bring in in about $66.1 million in the first year. According to Oakland County, of those funds, SMART would receive $33.3 million to maintain service and expand routes, the OPC would received $1 million, and the North and West Oakland Transportation Authorities would each receive $2 million. Additionally, $20.4 million will be allocated for new services—with the breakdown being $3.2 million for paratransit, $3.5 million for micro transit, $12 million for more routes and $1.7 million for improvements on existing routes.

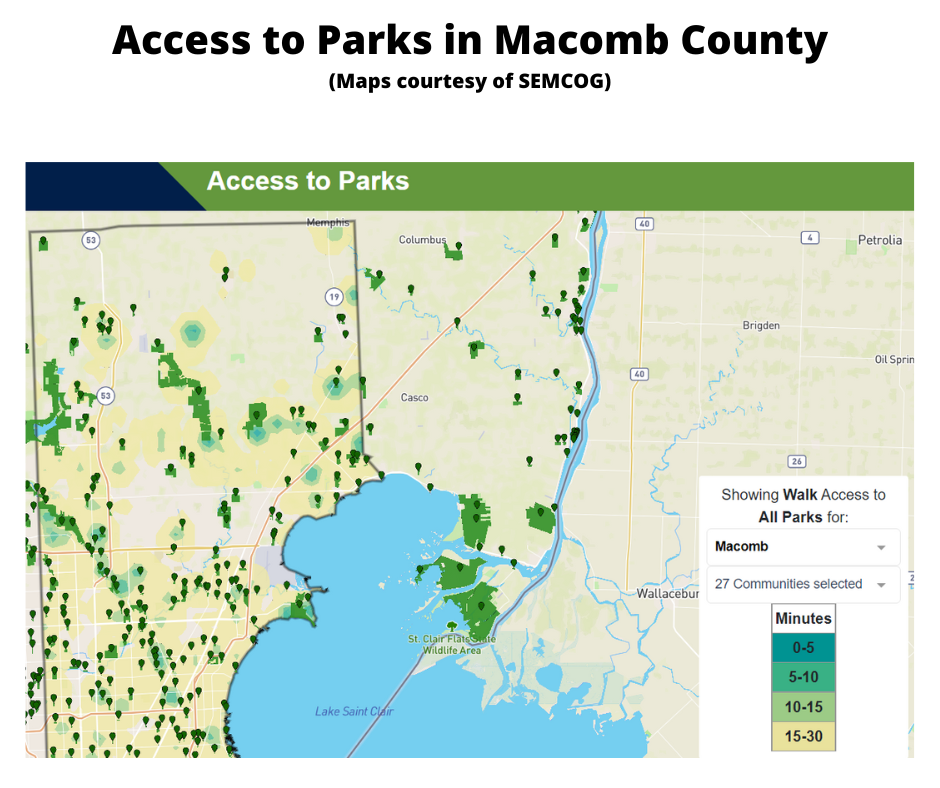

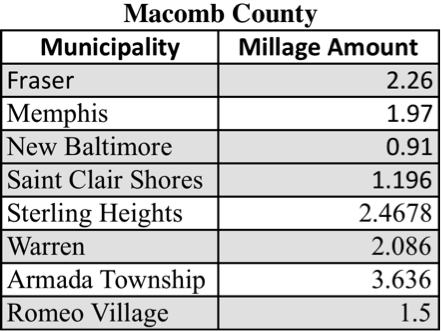

Macomb County is another fully opt-in county and has been one since 1995. In November of 2022 Macomb County also approved a 0.95 millage for transit but for five years; traditionally the millages were for four years. The most recent millage passed by 66 percent; in 2018 the millage passed by a margin of only 23 votes. With the passage of this millage, the funds are to support new routes, increased access to on-demand service and improved average wait times, according to SMART.

Wayne County is now the only opt-out county that SMART services. This November voters of opt-in communities approved a four-year 0.994 mill levy that will raise about $20.2 million in its first year, according to Wayne County. In Wayne County, there are 25 communities that opt-in to SMART services, according to the SMART website. Detroit is not an opt-in community as it has its own transportation network serviced by the Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT).

DDOT and SMART services do overlap in some areas, allowing users to easily travel to-and-from the state’s largest city on direct routes from certain other suburban communities; many of these stops are located along Gratiot, Michigan and Woodward avenues.

While transit in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties received continued support in the November 2022 election, the Ann Arbor Area Transit Authority did too in the August 2022 election. A new 2.38 millage was approved by Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti voters to support TheRide, which is operated by the AAATA. This five-year millage aims to improve and expand public transit service in the area. In addition to the passage of this millage, the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments also granted funds to support increasing transportation services between the cities of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, along with Ypsilanti Township.

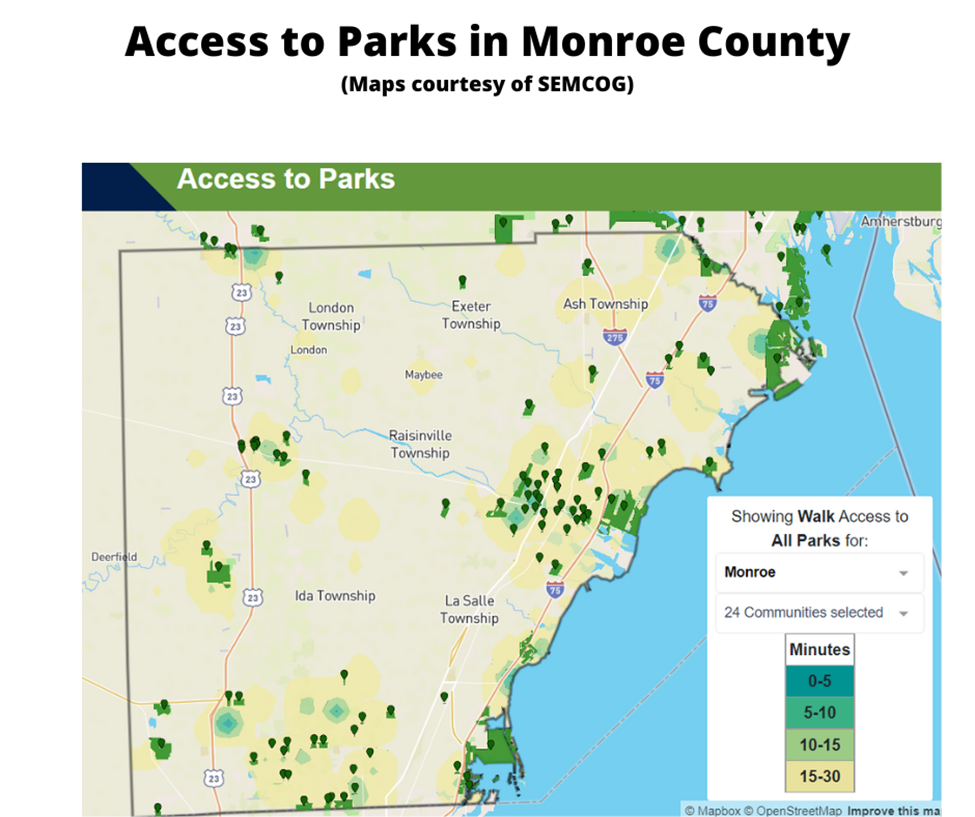

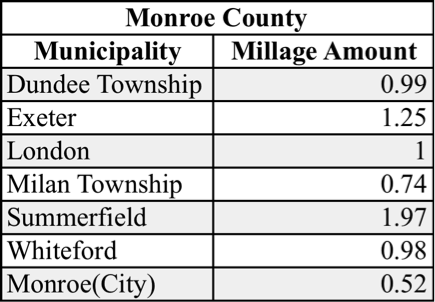

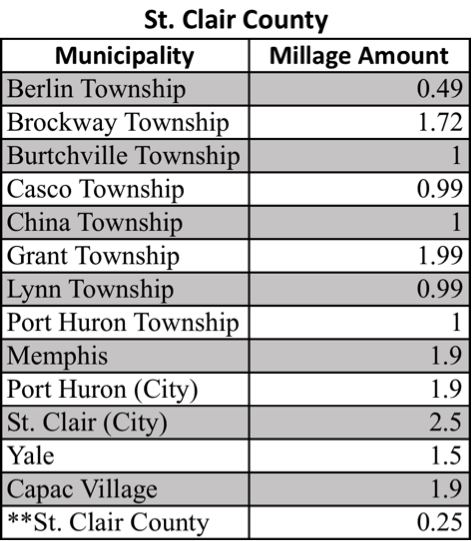

Between the AAATA, SMART, DDOT, NOTA, WOTA, OPC and then Livingston County’s Livingston Essential Transportation Service (LETS), Monroe County’s Lake Erie Transit service and St. Clair County’s Blue Water Area Transit services there are at least nine different public transportation providers in the seven-county region. Then, there is also the RTA, which is meant to oversee the yet-to-be developed regional services, and has the ability to leverage additional transportation millages if approved by voters (and voted to be placed on the ballot by RTA and county leaders)

So, while the recent transit millage approvals highlight increased support for public transportation in Southeast Michigan, it also seems the infrastructure for our fragmented public transportation network is only strengthening. Various mobility options must certainly be made available to meet the differing needs of the population, but benefits may be had when our public transportation and connectivity options are guided by a regional, forward-thinking mission.