Environmental injustice occurs when certain populations, typically those who are marginalized, and the environment are both harmed from certain actions. We have seen this occur with the Flint water crisis and we continue to witness it right here in Detroit. While pollution can come in many forms, it is air pollution that we are focusing on in this post and what is at least one factor in Detroit’s environmental injustice.

Before we dive into some of the sources of Detroit’s air pollution it is important to understand Detroit’s socioeconomic makeup. With a population of about 620,000 residents, 78 percent of the population is black, nearly 25 percent of the population is under the age of 18 and 32 percent of the population lives in poverty, according to the US Census Bureau.

Furthermore, according to the University of Michigan School of Public Health it is estimated that air pollution kills more than 650 Detroiters a year, with thousands more being hospitalized and children missing a disproportionate number of days at school because of illnesses and asthma.

According to the 2021 update on the State of Michigan’s “Detroit: The Current Status of Asthma Burden,” the asthma rate of the in the City of Detroit in 2019 was four times higher than the State of Michigan’s rate. Additionally, there were 1,458 asthma hospitalizations of Detroit residents in 2019.

Between 2017 and 2019, 71 Detroit residents died due to asthma. The rate of asthma mortality among Detroit residents was 31.4 per 1,000,000 population. The rate of asthma mortality in Detroit in 2017-2019 was about three times the rate for Michigan as a whole.

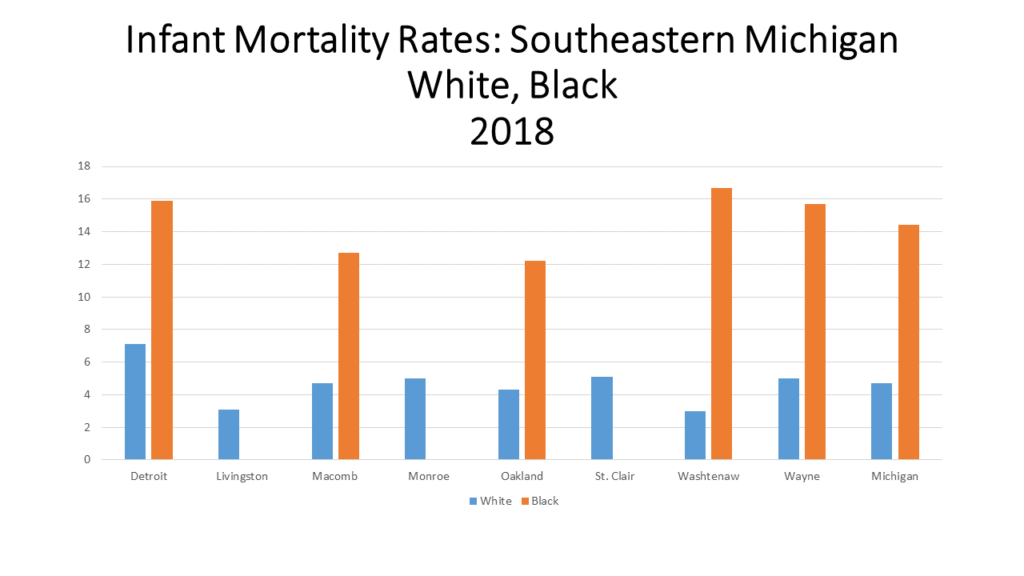

Now, when further digging into asthma rates el, the “Detroit: The Current Status of Asthma Burden,” states that in 2019, the rate of asthma hospitalization among Detroit’s Black population was 31 per 10,000 while the rate among Detroit’s white population was 7.9 per 10,000. Asthma hospitalization among Detroit Blacks were over three times that of Detroit whites. Michigan Blacks had over five times the hospitalization rate of Michigan whites.

According to the American Lung Association, the exact cause of asthma remains unknown, but there are certain factors that play a role in developing the disease. These factors include family history, allergies, viral respiratory infections, obesity, smoking, certain jobs and air pollution, especially including dust and mold.

As noted in our last post, there are several secondary particle pollution sources that have a negative impact on the area’s air quality in Metro-Detroit. According to climatetrace.org, a global non-profit organization that independently traces greenhouse gas emissions, some of the area’s highest emitters are an oil refinery, two steel plants, an airport and a powerplant. These emitters are:

Marathon Petroleum CO Detroit:

Ranked 378/80,188 Worldwide: for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Cleveland-Cliffs Dearborn Steel Plant

Ranked 296/80,188: for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport

Ranked 917/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Gerdau Monroe Steel Plant

Ranked 1,450/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Monroe Michigan Power Plant (DTE)

Ranked 37/80,188 for Carbon Dioxide emissions (CO2E)

Other secondary sources that contribute to particle pollutants in the Metro-Detroit are the the Mistersky and River Rouge power plants, highways, the Ambassador Bridge and Stellantis manufacturing plants in Warren and on Detroit’s eastside.

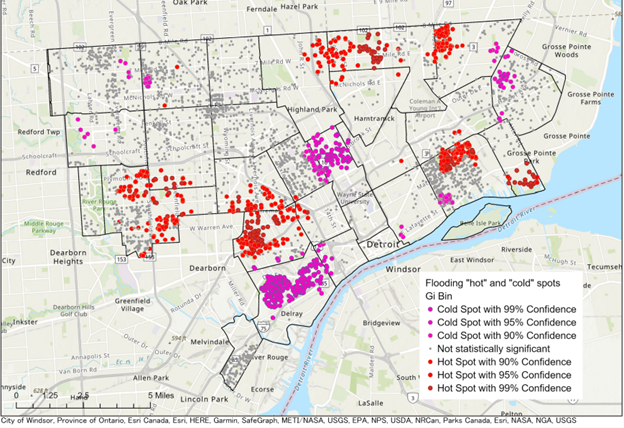

The media has long reported the history of the Detroit’s 48217 ZIP code, which is located in Southwest Detroit. With the Marathon plant and the DTE Delray and Mistersky powerplants, along with nearby highways and international trucking routes (Ambassador Bridge and soon to be Gordie Hower International Bridge), the amount of air pollution in this area is at concerning levels.

According to a recent released by the University of Michigan School of Public Health, between 2016-2021 the major source of PM2.5 ( which is fine inhalable particles, with diameters that are generally 2.5 micrometers and smaller) in the area was “mobile sources of emissions,” or vehicle exhaust and construction equipment, at 40 percent. Industrial sources of emissions also contributed a “sizable” amount to the PM2.5 levels, but were on the decline due to recent closures of coal-burning power plants and other facilities in the area.

Another area of growing concern is Detroit’s eastside, where the Stellantis production plant has not only grown to two production lines, but the amount of traffic has also increased due to the addition of a logistics warehouse that services the Stellantis plant. As has been noted in this and previous air quality posts, high traffic and industrial areas are major factors in both environmental pollution and an individual’s health.

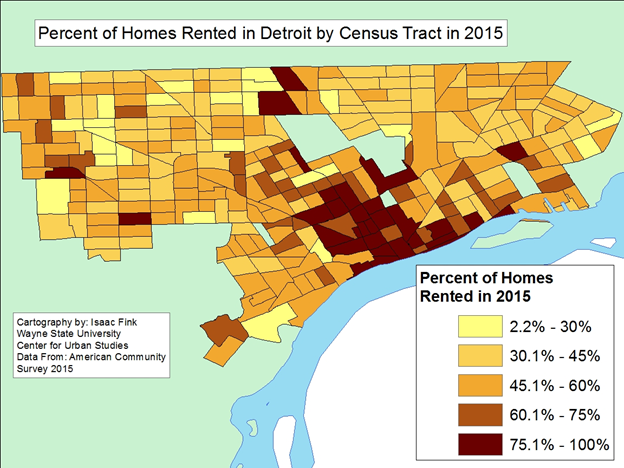

So, what we know thus far is that Detroit is a primarily a city composed of minorities, particularly African-Americans and Hiuspanics with a lower median income than neighboring communities in Southeast Michigan. We also know that in Detroit there are pockets of dedicated space for industry, whether it be manufacturing plants, power plants or other forms that push PM2.5 into the air. Poor air quality is not only a major concern for many Detroit residents, but also a reality. This type of environmental injustice has led to severe health problems for thousands of residents, both children and adults.

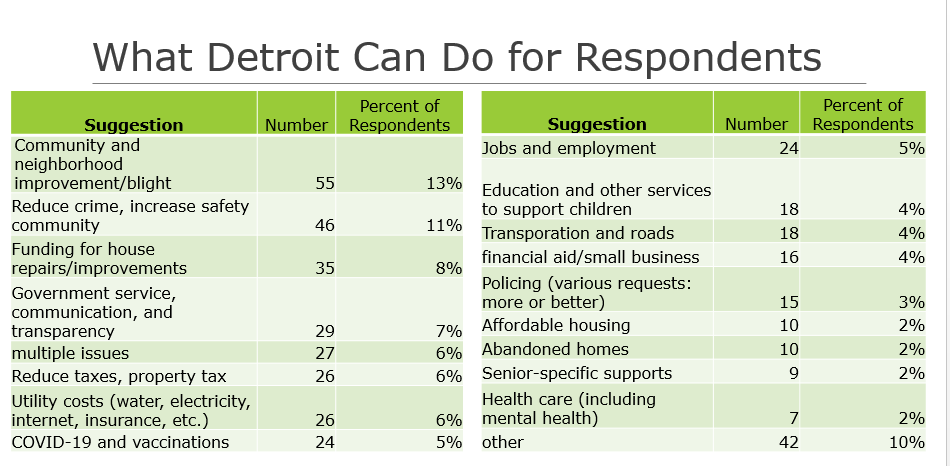

With strong regulations, from zoning to emission standards and even traffic regulations, we can work toward alleviating environmental injustices. However, as we continue to see at an increasing rate, pollution and other negative impacts on the environment have a long-lasting impact. Advocating for and taking steps to implement equitable solutions when it comes to housing, education and access to jobs is crucial.