Climate change is multi-faceted in both its causes and effects. In Michigan, and more specifically Metro-Detroit, many of the causes of these drastic shifts in weather patterns are the same across the globe— the continued use and overuse of fossil fuels, increased carbon emissions, desecration of natural resources. What are the effects?

Increased Average Temperature

Temperatures have already risen 2.5 degrees in Michigan. Summers are hotter, and heatwaves are stronger and last longer. Fast forward to 2100, summers in Isle Royale National Park are expected to 11 degrees hotter, according to statesatrisk.org.

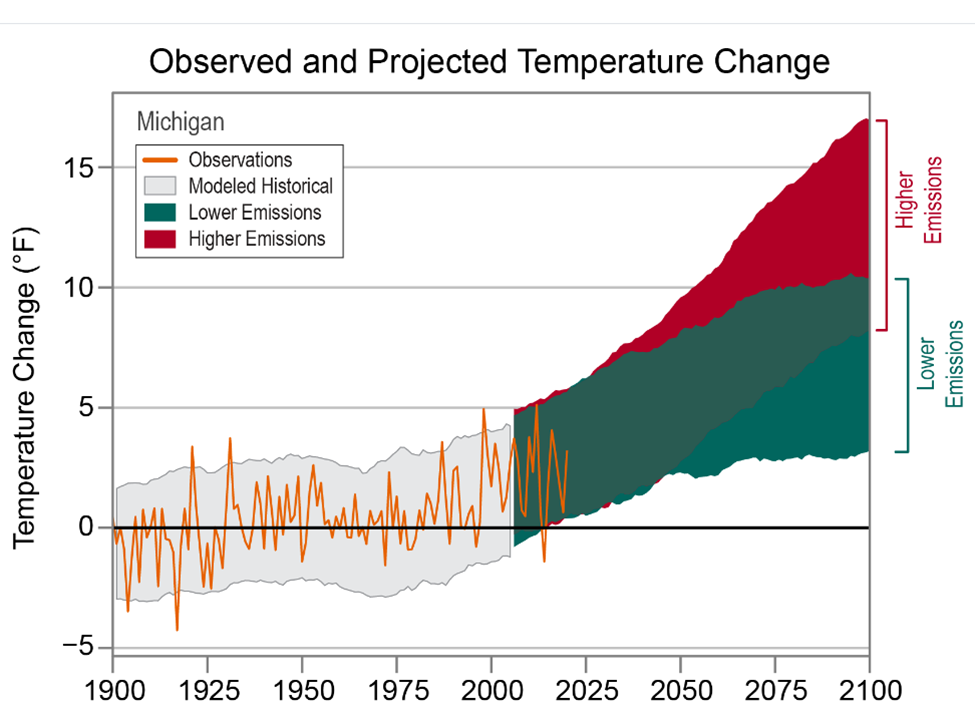

The chart below shows just how Michigan’s annual daily temperatures have changed since 1900 and how they are expected to change up to 2100, depending on the amount of emissions we continue to pump into the environment. The observed data is through 2020 and shows that Michigan’s average temperature has increased by nearly 3 degrees (Fahrenheit) over time. According to the data set from The Cooperative Institute for Satellite Earth System Studies and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), even with lower emissions temperatures are expected to increase in Michigan by a minimum of 3 degrees through 2100. That number could increase to at least 12 degrees though if the emissions we produce increase.

Increased Flooding

With increasing temperatures that means hotter air, which holds more water. More water means storms produce heavier rainstorms that are slower to move on, meaning greater accumulations of rain.

In 2020 30,000 residents of Southeast Michigan found their homes flooded. Six years earlier, in 2014, there was another great flood—these 100 year events happened within six years of each other.

According to the June 2021 report “Household Flooding in Detroit” by Healthy Urban Waters, in partnership with the Wayne State Center for Urban Studies and others, 43 percent of 4,667 Detroit households surveyed between 2012-2020 reported household flooding. Furthermore, in an online Detroit Office of Sustainability survey published in 2018, 13 percent of those survey reported they experienced flooding very often; 23 percent reported they experienced flooding somewhat often and 32 percent reported they experienced it occasionally. Additionally, a cross-sectional study published in 2016 of 164 homes in Detroit’s Warrendale neighborhood indicated that 64 percent of homes experienced at least one flooding event in during that, with many experiencing three or four events, according to the report.

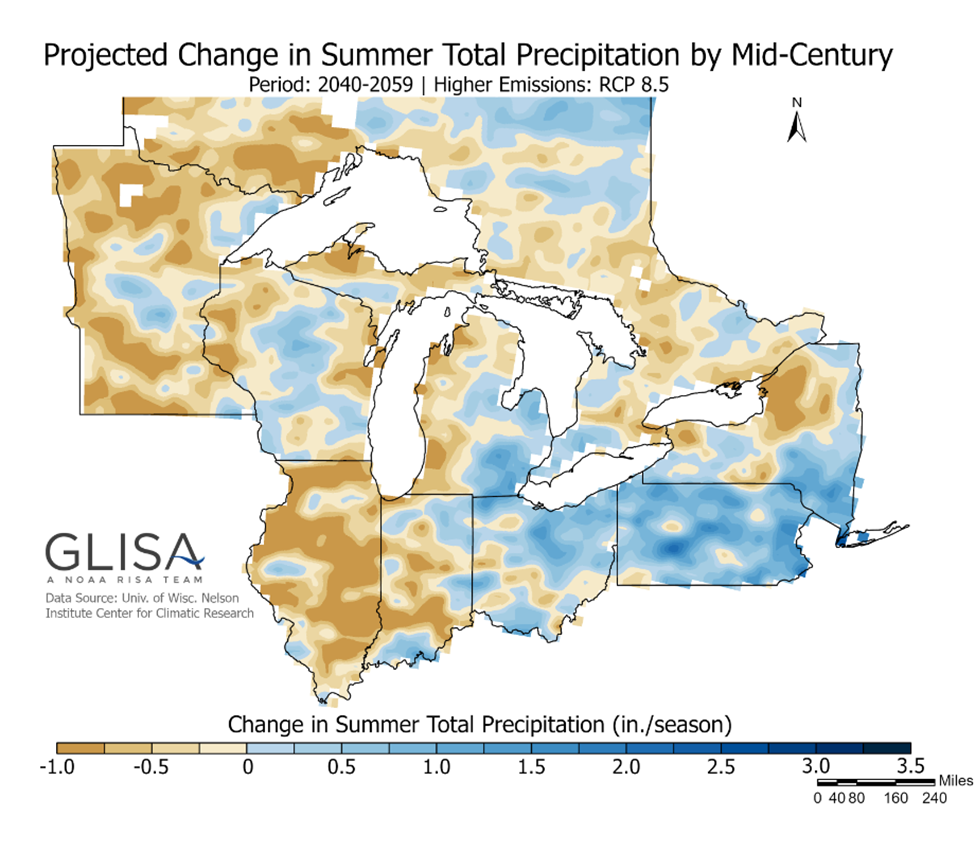

The map below is a projection map developed by the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments group that shows how precipitation is expected to increase in Southeastern Michigan and the middle of the state to about 2.25 inches between 2040 and 2059 with increased emissions. While Southeastern Michigan will face continued potential flooding events, the data prediction also shows that the western side of the state will have a decrease in precipitation.

An Increased Number of Heat Islands

A heat island, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is an area where heat is intensified due to structures, such as buildings and roads, that absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat far more than natural landscapes, such as forests and bodies of water. Urban areas, where these structures are highly concentrated and greenery is limited, become “islands” of higher temperatures relative to the outlying areas. Temperatures in such heat islands can be 1 to 7 degrees higher than neighboring areas. The Detroit metropolitan area contains heat islands.

Heat islands can be problematic, according to the EPA, because they can lead to increased energy consumption, increase the emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases and compromise water quality—all of which just further perpetuate climate change. Additionally, heat islands can have negative effects on human health.

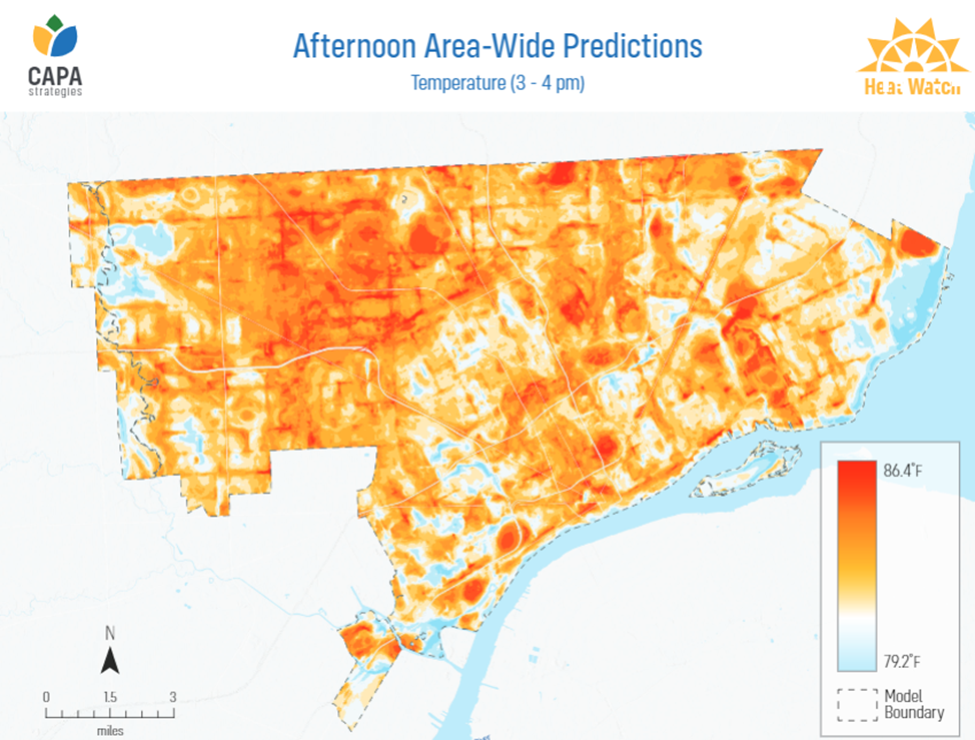

The map below was developed by the CAPA Heat Watch program, through a partnership with the National Integrated Heat Health Information System, NOAA Climate Program Office and the National Weather Service. This map was created from 2020 data and highlights how afternoon temperatures varied depending on the land coverage. For example, on the east side of the City, closer to the river, those areas have greater tree coverage so therefore tend to have cooler temperatures. However, areas with fewer trees, denser residential areas and wider streets have higher temperatures. As noted, this is how heat islands are created and these exist, for example, across the river from Belle Isle and several pockets on the City’s west side.

Less, or More, Ice Coverage

According to the GLISA, the depth of a lake impacts how rapidly ice can form. So with a shallower lake, there is a greater chance of ice coverage. While depth impacts the ability for a lake to freezer over so does temperature, and with temperatures above freezing there is less to no ice coverage. Less ice means moisture evaporates into the atmosphere easier, leading way to increased amounts of snow and rain in Michigan.

Also, according to the GLISA, water temperatures in the fall determine the amount of evaporation from the lake surface because the temperature difference between the air and lake surface temperatures can accelerate evaporation, with warmer water temperatures resulting in greater evaporation. According to the GLISA, “the evaporation removes latent heat from the surface, resulting in a cooling of the surface, and the potential for greater ice cover. For example, if the previous winter experienced low amounts of ice cover (more solar warming), higher evaporation rates (strong cooling effect) during the fall would lead to increased ice cover the next winter. Conversely, cooler water temperatures during fall leads to lower evaporation rates (less cooling) thereby decreased ice cover.”

The effects of climate change on Michigan and Metro-Detroit are apparent with impacts on the daily lives of many. Over the next year we will dig into some of the major contributors to climate change in the region, what policies are being developed to combat the impacts climate change (and how they will work) and what the future of Metro-Detroit may be with a new climate to adapt do.