Flooding in Southeastern Michigan continues to grow more common as weather patterns shift. In the summer of 2021 alone there have been at least three major flooding events, leaving hundreds of people with waterlogged basements, furniture and more. While the amount of rain certainly has an impact on the frequency of flooding, so does aging water infrastructure and various other household and neighborhood factors.

According to the June 2021 report “Household Flooding in Detroit” by Healthy Urban Waters, in partnership with the Wayne State Center for Urban Studies and others, 43 percent of 4,667 Detroit households surveyed between 2012-2020 reported household flooding. Furthermore, in an online Detroit Office of Sustainability survey published in 2018, 13 percent of those survey reported they experienced flooding very often; 23 percent reported they experienced flooding somewhat often and 32 percent reported they experienced it occasionally. Additionally, a cross-sectional study published in 2016 of 164 homes in Detroit’s Warrendale neighborhood indicated that 64 percent of homes experienced at least one flooding event in during that, with many experiencing three or four events, according to the report.

While we have the data on Detroit flooding, recent anecdotal tales tell us how cities throughout Southeastern Michigan—the Grosse Pointes, Dearborn and more—also continue to be affected by the surge of rain during storm events. Old infrastructure certainly impacts how a rain event affects a community, but so do other factors, such as the age of a home and if it is a rental versus being an owner-occupied unit.

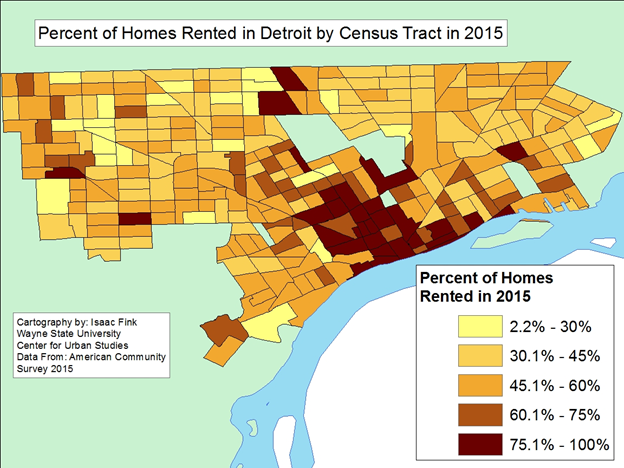

According to the “Household Flooding in Detroit” study, Detroit renters were 1.7 times more likely to report household flooding than homeowners. In a different study, the 2021 Detroit Citizen Survey, individuals were provided a list of home problems and asked to identify which ones apply to their house or apartment. There were 570 respondents to this question and of those a total of 1,111 problems were recorded; four of the five top problems (mentioned by 83% of householders) concerned water in the home (from plumbing to flooding).

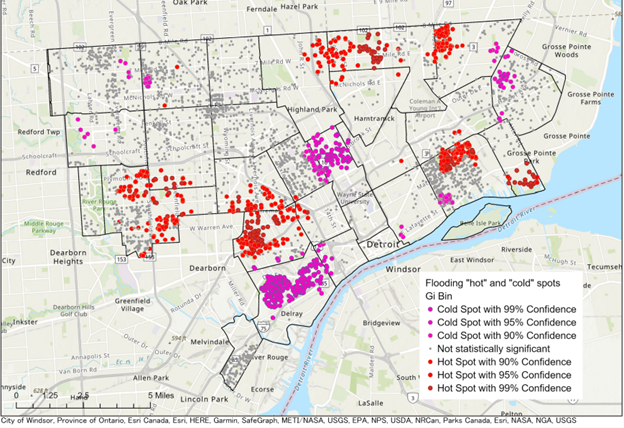

The first map above shows the hot and cold spots of flooding in Detroit using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic. Red dots represent “hot” spots of statistically significant clusters of homes that have experienced flooding. Purple dots represent clusters of homes that have not report flooding. The map reflects responses from a sample of 4,667 Detroit households who participated in the Center for Urban Studies’ Home Safety Assessment survey between 2012 and 2020. Among these households, 2,546 (42.75%) reported household flooding. As shown in the first map, the “hot” spots for household flooding in the City are located in clusters in the north end of the City, in the Jefferson Chalmers area near the river and Grosse Pointe Park, the East Village/Indian Village areas and in the Warrendale/Rosedale Park/Michigan Marin areas. Also note, some of these “hot” spot flooding areas in Detroit border other areas that have experienced flooding during recent rain storms, such as Dearborn and Grosse Pointe Park.

The second map shows 2015 data of the percent of renters, by Census tract, in Detroit. Those Census tracts with “hot” flooding spots also have at least 30 percent of the population renting and data shows that neighborhoods with a larger proportion of renters (compared to owners) and homes built before 1939 are more likely to experience household flooding. According to the Census Bureau, about 33 percent of the City’s housing stock was built before 1939.

The flooding study also found that primarily Black communities were found to be at high risk for household flooding; according to the Census Bureau, 78 percent of Detroit’s population is Black.

So, while we know that flooding affects some communities in Southeastern Michigan more than others and that the risk for the region will only increase as the effects of climate change grow, there actions that can be taken to mitigate flood damage. Updating water and sewer infrastructure to increase its reliability is a high, yet expensive, priority to help decrease the risk of in-home flood events for communities at-large. Investment in green infrastructure, such as rain gardens, is another option as is identifying parts of communities most prone to flooding and further investigating the specifics behind it. But again, these require time and money and municipalities regularly struggle to maintain their infrastructure, let alone allow for major upgrades.

Infrastructure investment is necessary, but so are larger actions to help slow the affects of climate change.