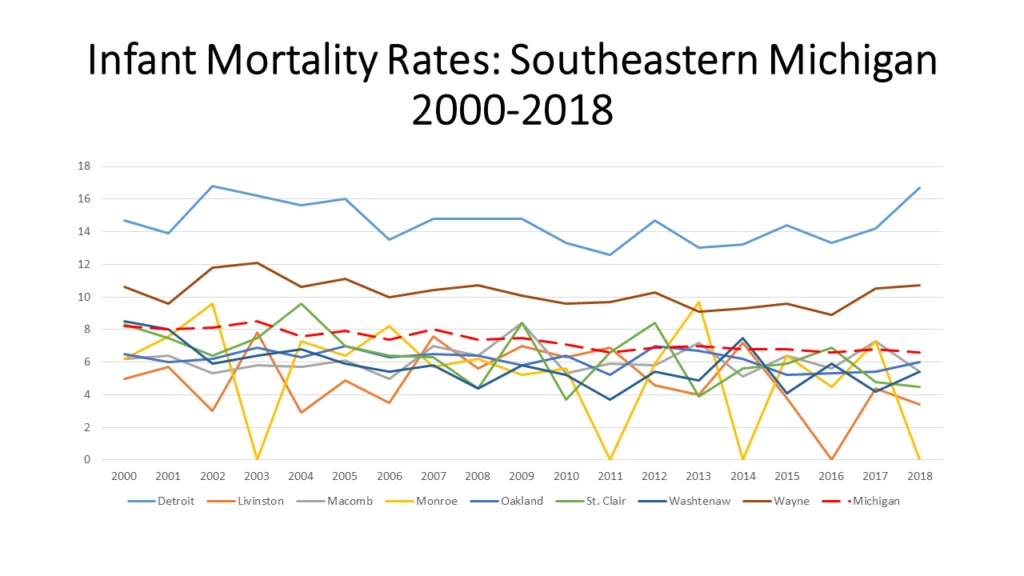

Michigan ranks 36th in the country in infant mortality and the City of Detroit has the highest number of infant deaths in the State, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. In 2018, the most recent year for which data was available, Detroit’s infant mortality rate was 16.7, the highest its been since 2002 when the rate was 16.8 These two rates translate to 9,476 (2018) infant deaths and 14,187 (2002) infant deaths, respectably. The infant death rate is the number of resident infant deaths divided by total resident live births X 1,000. Infant deaths are deaths occurring to individuals less than 1 year of age.

As shown in the first chart below, Detroit infant mortality rates are consistently much higher than those of any county in Southeastern Michigan, and any other county in the State. Detroit’s infant mortality rates are also consistently higher than the State average. And, while the State’s infant mortality rates have been declining overall since 2000 Detroit’s rate has increased 3 points since 2016. It is important to remember that over 50 percent of children in Detroit families live below the poverty rate, far higher than elsewhere in the state.

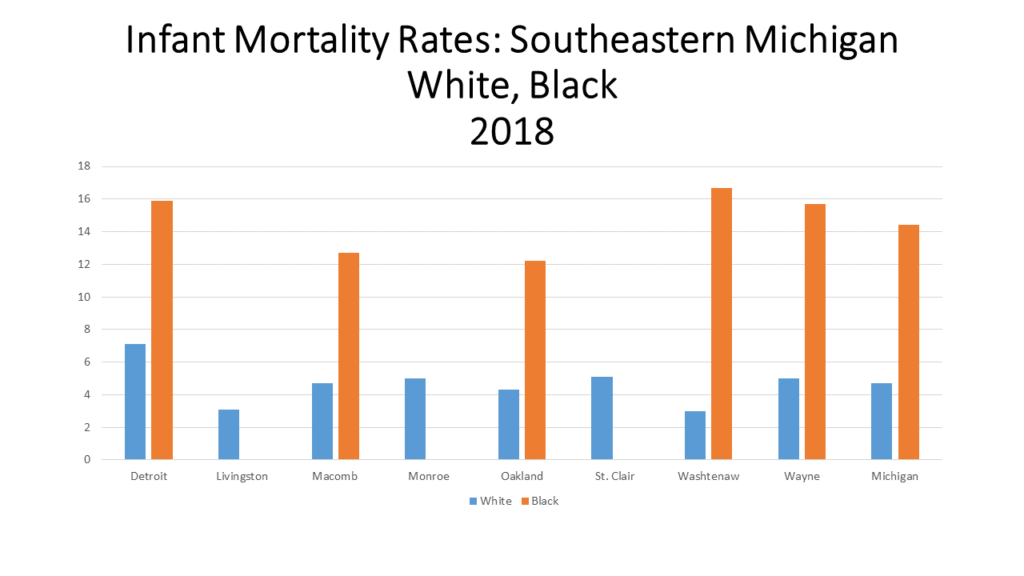

Monroe and Livingston counties have regularly had the lowest rates; in some years not enough data was available for a rate. While we know that Detroit and Wayne County’s infant mortality rates are much higher than those in Monroe, Livingston and Washtenaw counties we also know that race plays a role in infant mortality rates. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, African Americans • Have 2.3 times the infant mortality rate as non-Hispanic whites;

•Are 3.8 times as likely to die from complications related to low birthweight as compared to non-Hispanic white infants;

•Had over twice the sudden infant death syndrome mortality rate as non-Hispanic whites, in 2017.

Additionally, in 2017, African American mothers were 2.3 times more likely than non-Hispanic white mothers to receive late or no prenatal care. The evidence of these statistics are also apparent in the second chart below.

In 2018, the most recent year for which data was available, the infant mortality rate for black babies in Detroit was 15.9 while for white babies it was 7.1. That gap between infant mortality rates of white and black was even larger at the State level ( 14.4 for black babies and 4.4 for white babies) and at the county level in the region (compared to that in Detroit), where median incomes tend to be higher. Furthermore, Detroit’s overall infant mortality rate is likely the highest in the State because it has among of the highest percentage of black residents. According to the US Census Bureau, 78 percent of Detroit’s population is black, 39 percent of Wayne County’s population is black while 1 percent of Livingston County’s population is black and 2 percent of Monroe County’s is black. Statewide, 14 percent of the population is black.

Not only should the increasing infant mortality rates of Detroit and Wayne County be of concern, but so should the causes. As alluded to above, race and income are contributing factors to infant mortality rates, as is racism. According to the Michigan League for Public Policy’s report “Strong Moms for Thriving Babies: Right Start 2020“ issues such as poverty and racism must be addressed in order for local infant mortality rates to decrease. Recommendations to do this include extending Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum; allowing for and enhancing reimbursement rates; increasing the number of high-quality home visiting programs to establish healthy starts for families by offering moms and their children, valuable health screenings and connecting families; restoring Michigan’s Earned Income Tax Credit; and advocating for paid paternity leave.

Statewide, a $12.6 million annual budget for the new program “Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies” was approved as part of the 2021 budget. This program is aimed at decreasing the infant mortality rate while providing the resources in order to accomplish that goal. Components of this program include:

• Plans to expand healthcare coverage for a mother to a year;

•Moving a woman’s first postpartum visit to within three weeks, with a comprehensive visit within twelve weeks;

•Requiring implicit bias training for medical professionals;

•Expanding home visits;

•Allowing the woman to chose what form of birth control works best for her.

The problem, however, is that divided evenly this would provide only about $116 per child under one. If it were concentrated on only the 19% of children in poverty, this would set aside a bit over $500 per child. Is it likely this is enough to make substantial change?