In Southeastern Michigan there are eight main regional governing bodies, most of which rely heavily on the counties to fill out the structures. These governing bodies are: the Huron Metro-Parks, the Detroit Institute of Arts Authority (one in each Macomb, Oakland, Wayne), the Detroit Zoo Authority (one in each Macomb, Oakland, Wayne), the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transit, the Great Lakes Water Authority, the Regional Transit Authority and the Detroit Regional Convention Center Authority and the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG).

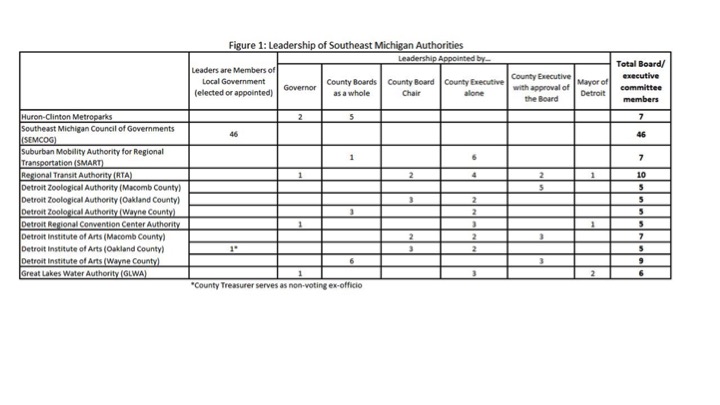

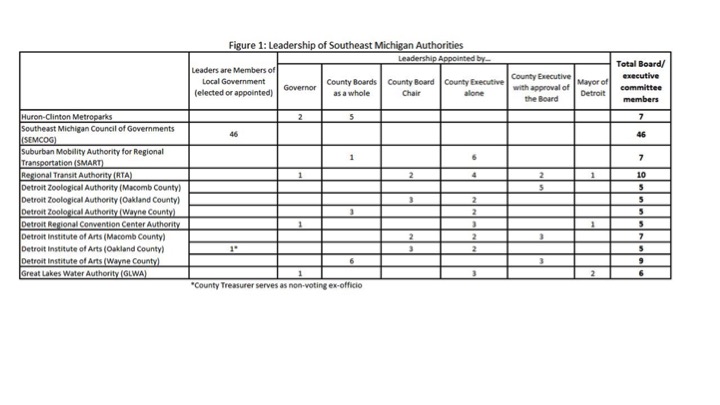

Each of these regional governing bodies are made up of individuals who have been either appointed by a County Board of Commissioners, a County Executive, or a combination of both. County Executives have the most appointment authority. With the exception of SEMCOG and the Huron-Clinton Metroparks County Executives have some type of appointment authority with each regional body. This power, for both the counties and the County Executives, is one of the structural patterns that exists in this region’s fragmented group of regional authorities. The City of Detroit Mayor and the Governor have roles in the various authorities, but to a much lesser extent.

Another pattern that exists is that none of these regional bodies allow for their seats to be filled by elections, causing a lack of accountability and an increased ability for personal interests to be pursued. Instead of electing individuals to govern these public bodies, dozens of public officials are hand picking individual candidates to fill the seats. This process, for each regional authority, allows for stakeholders to pursue these new roles to exercise their influence over the governing body. This new layer of politics is also coupled with the fact that the elected officials, particularly county officials, can further their personal agendas with the appointing powers they have been given in this rise of fragmented regionalism.

With eight various regional authorities now overseeing the governance of everything from our cultural institutions to water, the way in which these bodies are structured in terms of members vary greatly. For example, when looking at the Detroit Institute of Arts authorities for the counties (Macomb, Oakland and Wayne) none of the three have the same number of individuals on their board (click here for the history of the art authorities). Despite that each board has been set up for the same purpose-to oversee the DIA millage founds levied in their county-how they are structured vastly varies. In Wayne County, the Board of Commissioners have the authority to appoint six of the nine members; the Board then confirms the Wayne County Executives three appointments. In Oakland County the Board Chair appoints three members to the Art Authority and the County Executive appoints two. In Macomb County there is a seven member board, the County Board Chair appoints two members, the County Executive appoints two members and three members are appointed by the County Executive, with approval from the Board of Commissioners.

The Detroit Zoo is the only other regional entity with three different boards (one per county in which the operational millage is levied) that serve as its overall governing authority. The number of members who serve on each County board for zoo does not vary, but a look at the total number of representatives on each board, whether it be a Zoo Authority or SEMCOG greatly varies between 5 members to 47 members (SEMCOG is the only one with 46 members). The total number of representatives on each regional authority is shown in the chart above.

The legislations that created other regional authorities states each authority will only have a single governing body. However, even with those bodies we see the number of representatives vary, as do appointing authorities, which are often times defined in the body’s articles of incorporation.

These varying structures and appointment authorities again show the fragmented nature of our regional authorities. Until the financial downfall of Detroit began regionalism never strongly existed in Metro-Detroit. However, that has since changed as these bodies emerged out of economic and functional necessities.

Due to the manner in which these regional governing bodies emerged ( for more historical context click here) there is no cross functional consolidation of the kind envisioned by proponents of metropolitan governance. This functional differentiation is consistent with the polycentric nature of metropolitan Detroit, the decades-long animosity between Detroit and its neighbors, and persisting racial tensions.

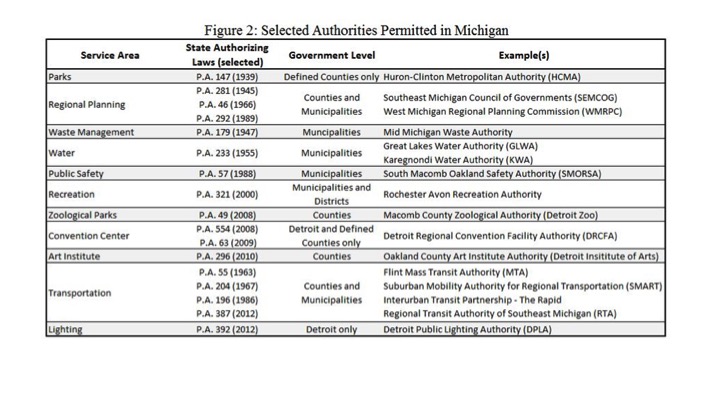

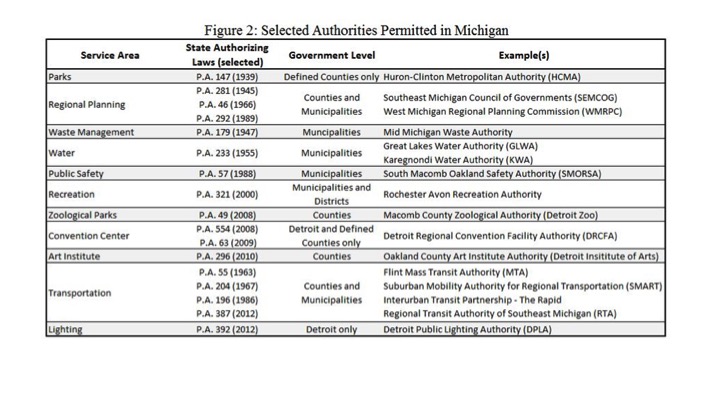

For additional historical context on the topic of regionalism in Southeastern Michigan, below is a table highlighting which state legislations gave way to each regional authority.