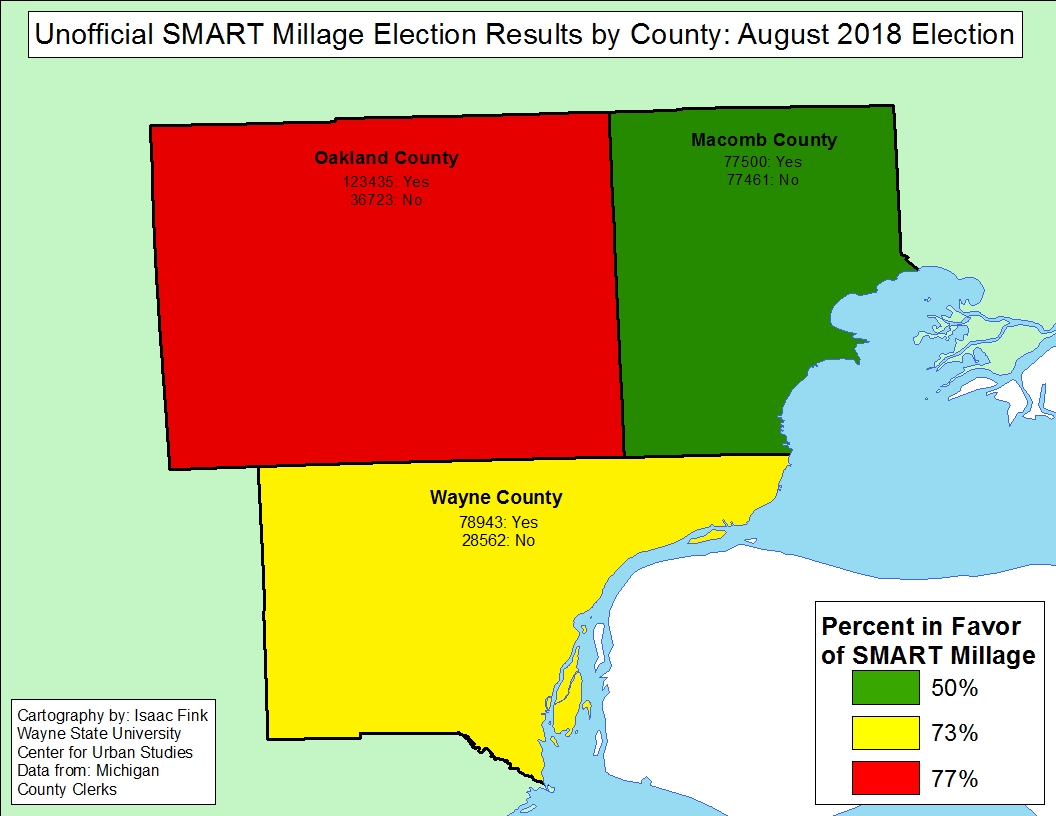

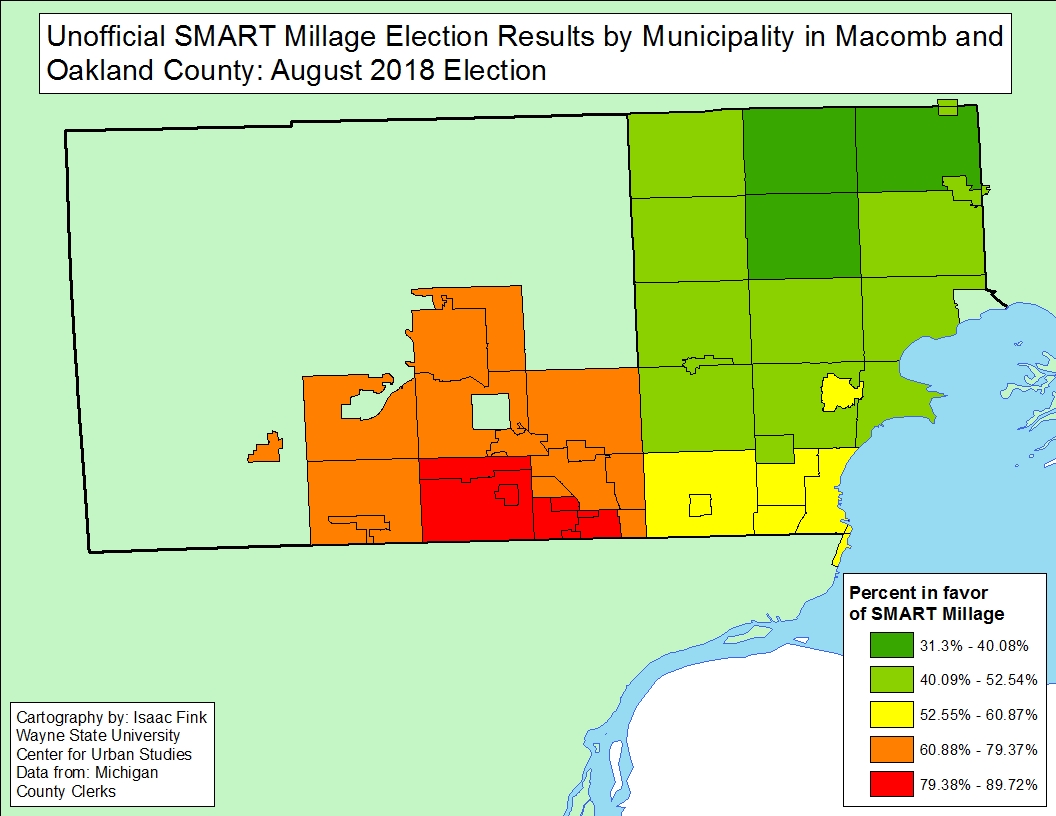

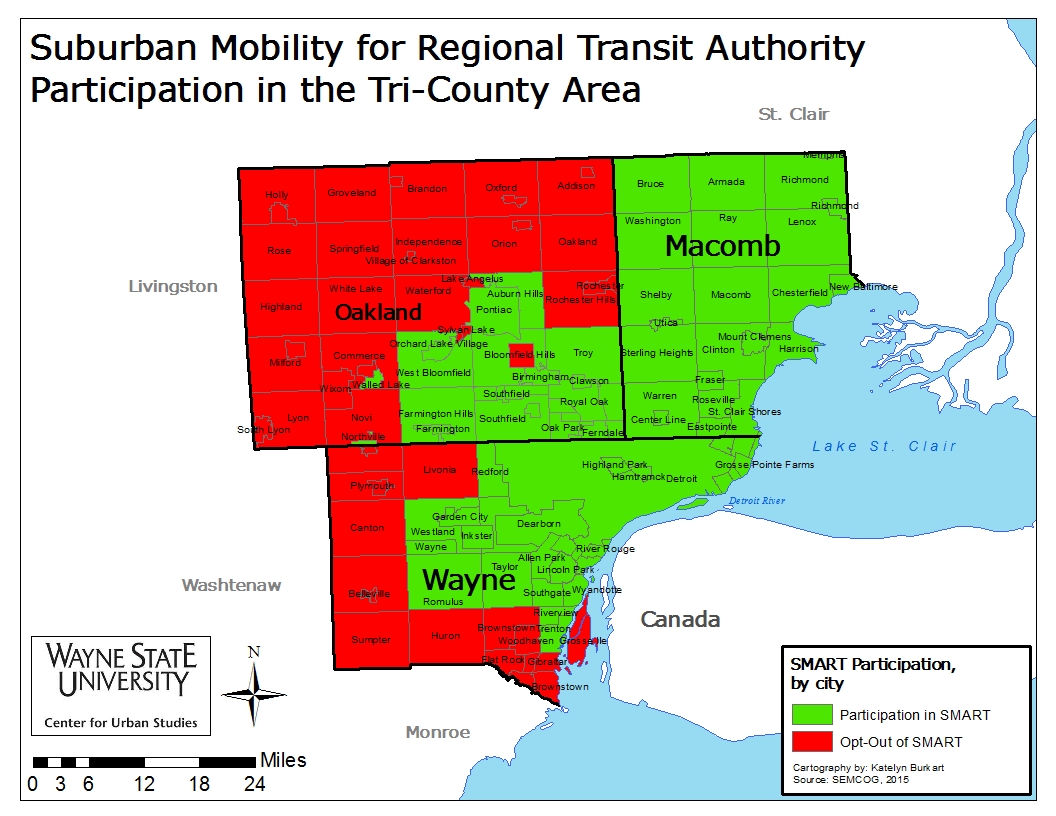

The fate of public transit in Southeastern Michigan continues to remain unknown. While the Suburban Mobility Authority For Regional Transportation (SMART) millage passed in communities throughout Oakland and Wayne counties and, just barely, in Macomb County the cohesion amongst public figures and, most importantly, the public continues to disintegrate. The continued outspoken opposition against the Regional Transit Authority (RTA) by Oakland County Executive Brooks Patterson and Macomb County Executive Mark Hackel tend to gain the most attention, but the near death of public transit in Macomb County should speak even louder. In Macomb County, when a SMART millage goes before voters the entire county must either approve or vote it down. Just last month the voters of Macomb County were asked to approve a SMART millage renewal. The voters did approve the millage renewal, but by a mere 23 votes, even though Hackel was urging for a “yes” vote on this proposal. Four years ago though, when Macomb County voters were asked to approve a millage increase, from 0.59 mills to 1 mill, the passage rate was 60 percent. This approval came before the 2016 RTA millage request that ultimately failed. This RTA millage proposal passed in Wayne and Washtenaw counties, where support was a given, and continues, by the elected officials and businesses, while it failed in Macomb and Oakland counties.

Two years later, officials still can’t come to a consensus on what the RTA proposal should be, which is why it will not appear on the November ballot.

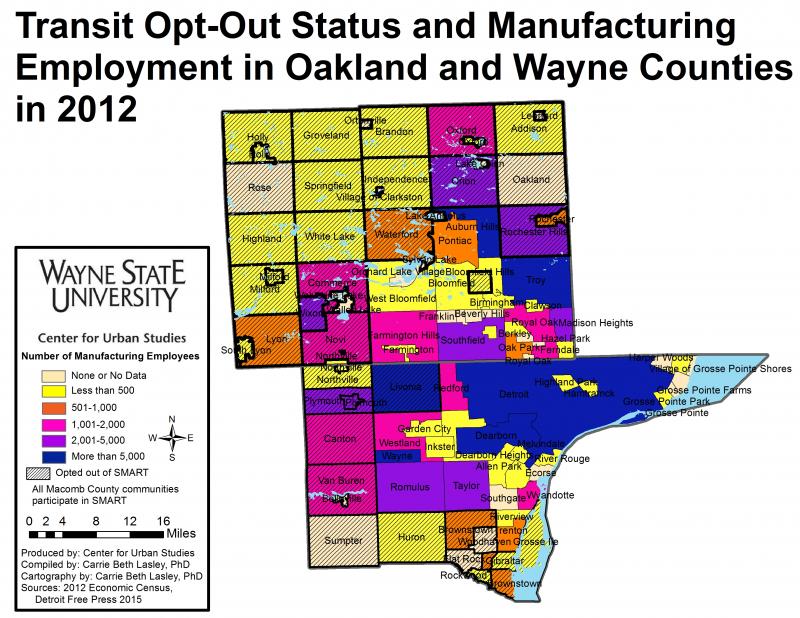

The stories amongst elected officials remain the same, Patterson and Hackel don’t support transit in the form of the RTA, Wayne and Washtenaw county and Detroit officials see the need to expand on current systems and the messaging transit advocates have tried to push for years is not getting through. With the SMART millage passage transit options will continue to be provided in areas of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties. Additionally, the Detroit Department of Transportation and SMART continue to strengthen their relationship to provider faster and broader connectivity for transit users. However, the negativity propagated about regional transit from Patterson and Hackel seems to be trickling down to voters. It is vital that regional community, meaning the voters, comes together to push for a robust system that allows citizens greater opportunities to travel to jobs, educational institutions and health care providers. There must be support for a system that encourages economic growth, and most importantly, breaks down barriers that currently exist in Southeastern Michigan. To do this, citizens need to educate themselves on both sides of the regional transit debate, grow their understanding on what transit means for a region and not be afraid to speak against the loudest in the room.

As to public officials, one wonders when those officials who do support transit—those in Wayne County, Washtenaw County and Detroit—will realize that they can innovate without their recalcitrant neighbors to the north. A thriving transit system propelled by these governments will support the rapidly evolving growth economy along the east-west axes of I-94 and I-96/U.S. 23, even if our northern neighbors wish to lag. Let’s proceed intelligently and incrementally, if regional and rational are not feasible at this time.