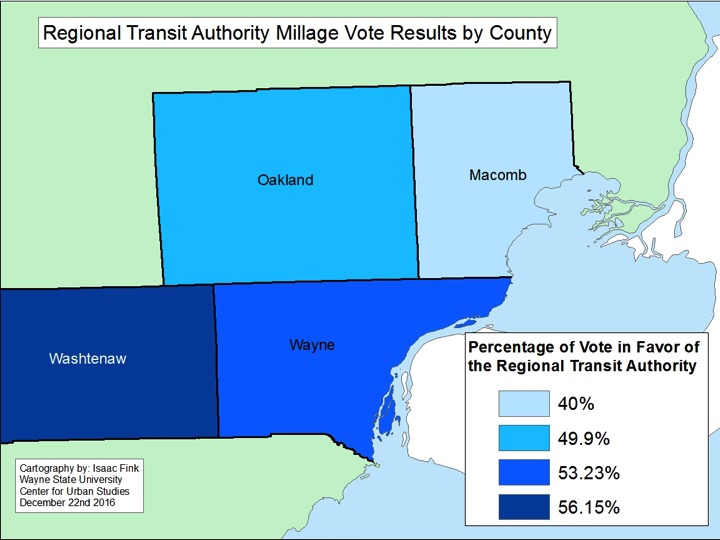

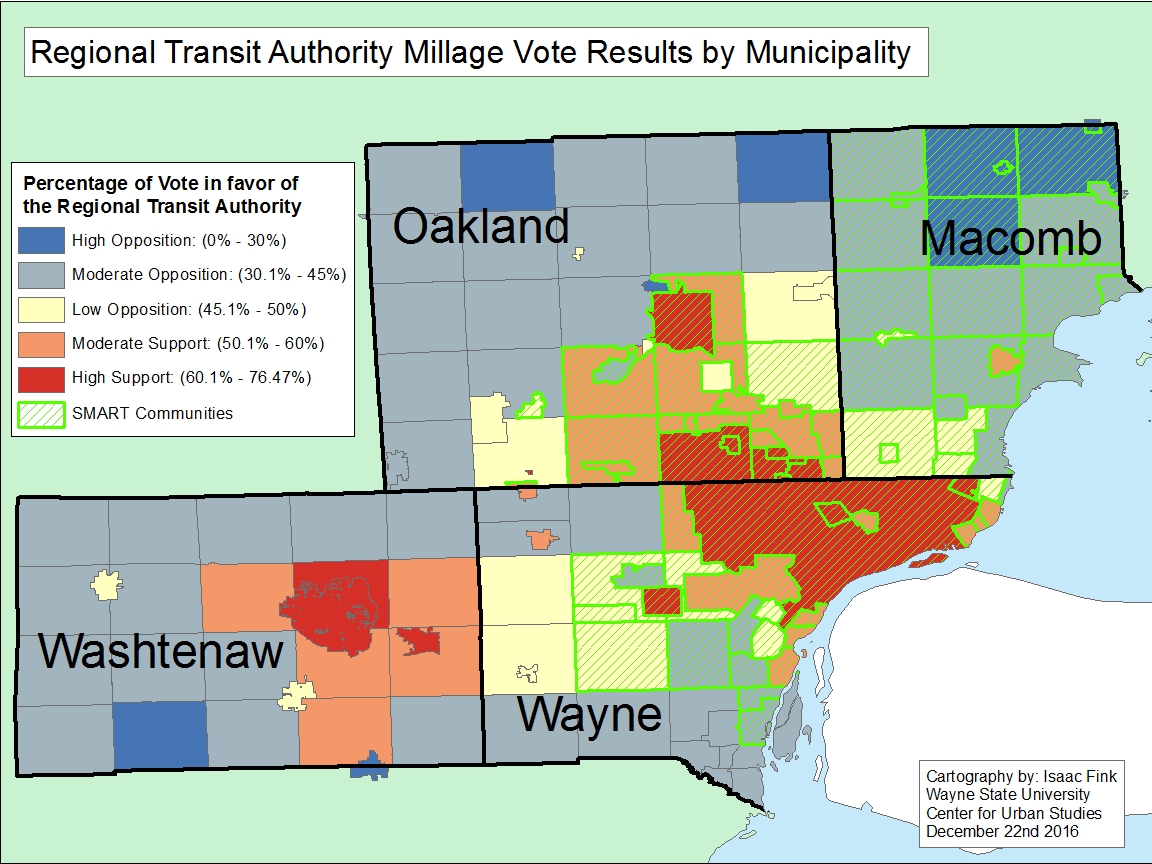

Throughout the Metro-Detroit region there are multiple millages being levied to support regional entities, most of which were born out of Detroit’s bankruptcy and the economic downturn. When some of these millages were originally levied, the initial intentions expressed to the public were that they were for only a specific amount of time, such as with the Detroit Institute of Authority (DIA). However, the Detroit Zoo for example passed a 0.1 millage in 2008, and then came back to voters in 2016, two years before the 10 year millage was set to expire, and asked for a renewal. The 0.1 millage renewal passed, and this public support for the Detroit Zoo continues to be levied; the cost of the Zoo millage for a home valued at $100,000 ($50,000 taxable value), is $5. We have also seen the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) continuously seek millage renewals and increases, the most recent being a 1 mill renewal for four years that was approved by voters in 2018.

Now, as the end of 2019 nears, the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) recently announced it is up against the clock to put millage renewal language on the March 2020 ballot. The 10-year millage was originally approved by voters in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties in 2012, and it was stated at that time that it was a one time request, allowing the museum time to build up its endowment for long-term financial support of operations, according to news articles of 2012 and present. Now seven years into the one-time millage, DIA officials have announced a 10-year renewal is necessary to continue offering the services the public has come to expect. In order to do this the three Art Authorities in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties (which were born out of articles of incorporation crafted and approved by the corresponding Board of Commissioners) must approve the ballot language. Just last week the Wayne County Art Authority approved putting the 0.2 mill renewal on the ballot, Oakland County is expected to debate the potential millage renewal later this month and the Macomb Art Authority will do so on Dec. 3.

As discussions again begin to ramp up over whether another regional millage renewal is necessary, it is important to consider what benefits the current tax dollars levied for the DIA may have created the region. In addition to free general admission for Macomb, Oakland and Wayne residents additional benefits can be covered under three main areas: investment in schools (free field trips with bussing, teacher professional development, and curriculum development), investment in the senior population (free group visits for older adults on Thursdays with free transportation and special programs), and investment in community partnerships (Inside/Out program, partnerships with area non-profits).

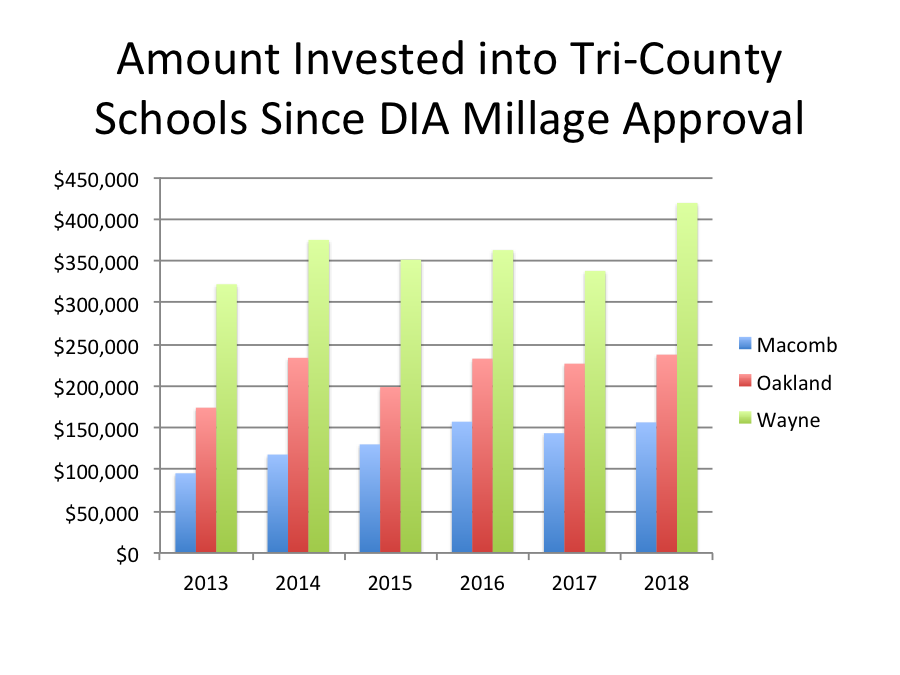

The first chart below shows the amount of money invested into the schools in the region by county and by year. In total, between 2013 and 2018 392,231 students in the tri-county region have had access to the school programs now offered by the DIA, with that investment totaling about $4.3 million. Of the three counties the most amount of money has been invested into the Wayne County schools, with that total being about $2.2 million. Wayne County has the highest population of the three counties. It should also be noted though that investment into these various programs in the counties requires participation from the residents.

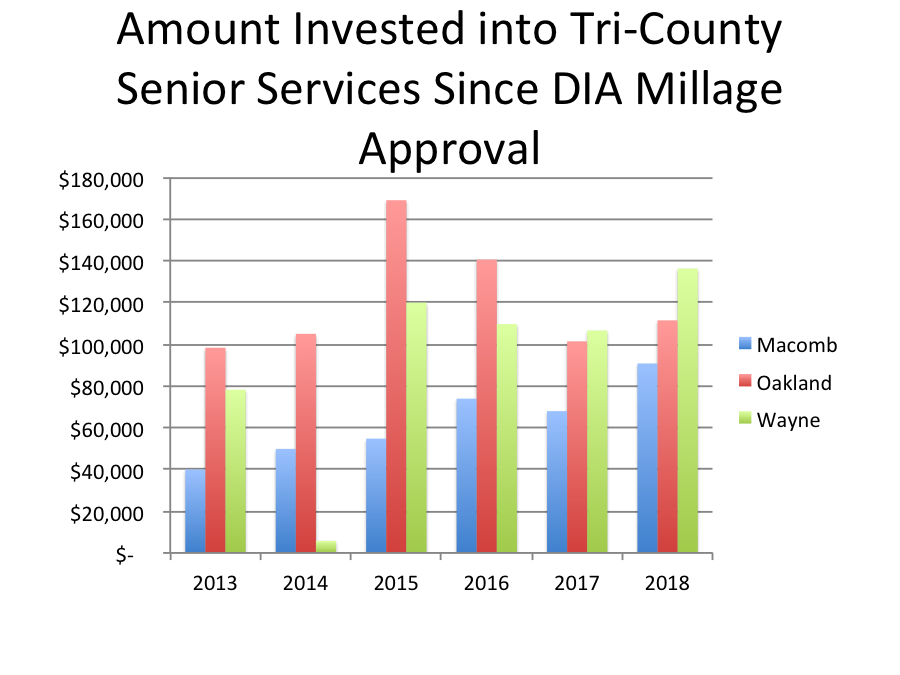

When looking at the amount invested in the senior programs since 2013 that total is about $1.7 million with the total number of seniors being reached by these special programs being 32,422. The largest investment with the senior programs since the millage has been in Oakland County with a total of $725,362 being invested into the senior population.

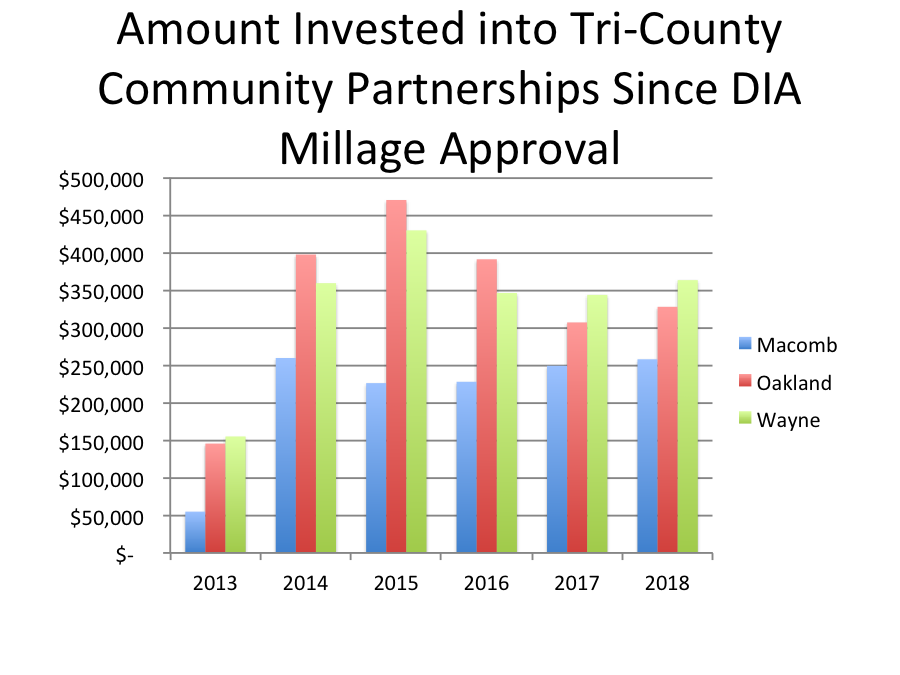

Finally, the area where the most investment has been made is in the community partnerships area. Between 2013 and 2018 about $5.3 million was invested. The largest investment was in Oakland County at about $2 million. In Wayne County $1.9 million was invested, and in Macomb County about $1.3 million was invested.

It appears a new trend is emerging where millages will be needed to support regional entities and interests (the Zoo, the DIA, transit) along with day-to-day services in some cities and counties. For example, in Detroit there are currently discussions about a March ballot proposal to levy additional funds to move blight removal in the city along at a much faster pace. In Macomb County residents will asked to decide if they want to pay additional taxes in order to build a new jail. So it may be even more important for taxpayers to understand what additional taxes are appearing on their tax bill and what their priorities are. In the coming weeks we will look at the additional taxes residents pay in certain communities throughout the region to shed further light on what tax bills are now looking like.