For our cities to function effectively, taxes must be levied to support services vital to their survival. Here we examine the same hypothetical Eastpointe property discussed last week to portray what additional taxes—beyond general school, city and county operating millages—are levied to provide services to this city’s residents.

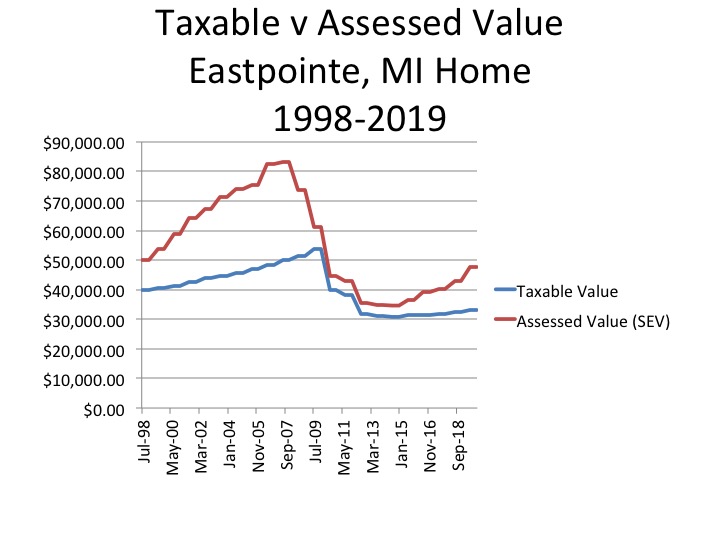

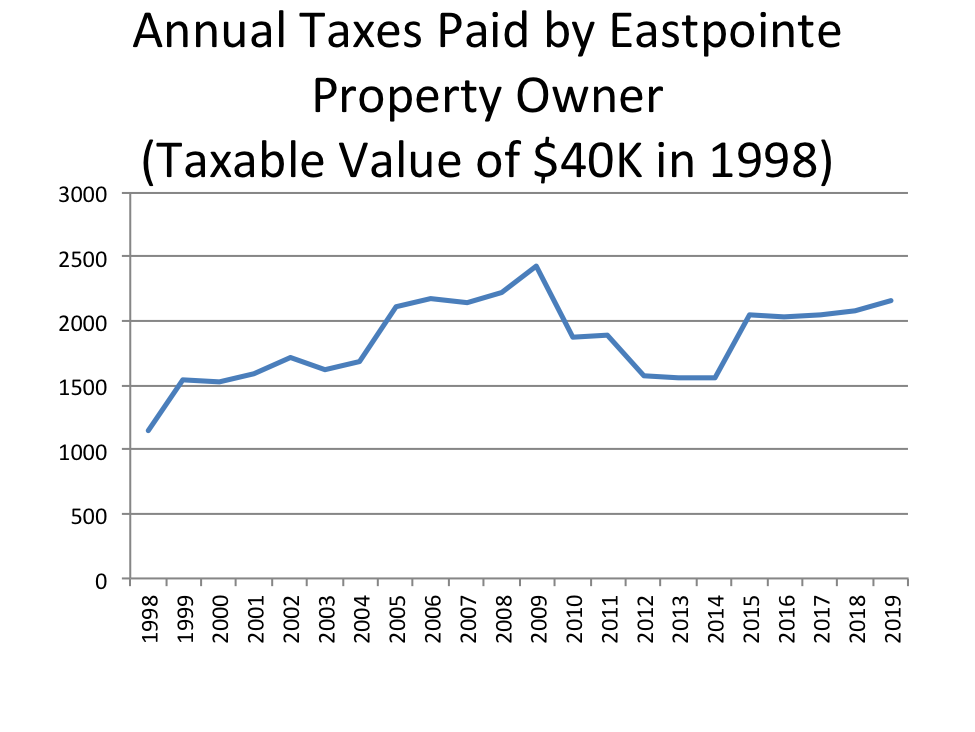

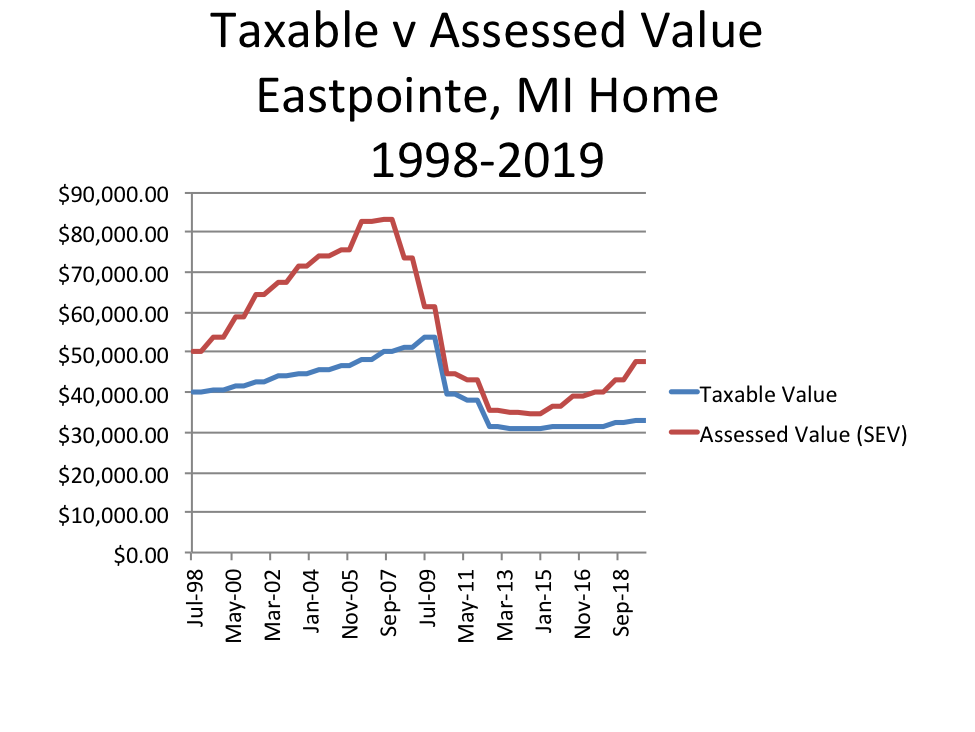

The first chart below shows that from 1998 to 2009, the total dollar amount this hypothetical property owner was paying in taxes gradually increased. This can be attributed to two factors. First, both the assessed and taxable value of the property (shown in Chart 3) gradually increased during that time, meaning more property tax revenue for local governments. Second, voters approved at least one new major tax levy during that time. This major tax was approved in 2005 and allowed the city to collect a special levy of up to 7 mills for public safety. For this hypothetical household, that levy equaled $327.94 in 2005. In contrast, a decade later, that same special levy brought in $219.08. The decline was due to the fact that the taxable value of the property plummeted, along with the assessed value, in the wake of the Great Recession.

As shown in Chart 1, the amount of taxes this hypothetical property owner paid peaked in 2009 ($2,432.30), which corresponded with the peak taxable value of this home ($53,599). The subsequent decline in tax bills occurred despite new service assessments approved by Macomb County voters. For example, it was in December of 2008 when the regional millage for the Detroit Zoo began to appear on the tax bills for this property, which by then had a taxable value of $51,340.41, costing the homeowner $5.13. Tax data from the City of Eastpointe also shows that this new assessment was much lower than existing county assessments such as the Huron-Clinton Metroparks millage, costing this hypothetical property owner $11.01 in 2009,and the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transit (SMART) millage, which cost the homeowner $30.29 that year. Chart 2 below presents a timeline of the changes in county-wide and city millages that affected Eastpointe taxpayers.

Chart 1

**(Note-all taxes on the Eastpointe tax bill are included in the graph above)

Chart 2: Timeline of Eastpointe, Macomb County Millages and Increased Millage Renewals

1995

- Suburban Mobility Area Transit Authority (SMART): 1 mill (quadrennial countywide renewals approved at varying rates; the most recent was narrowly approved in 2018)

2005

- Eastpointe Public Safety: 7 mills (part of general city operating millage starting in 2016)

2008

- Detroit Zoo: 0.1 mill (2008-present; renewal approved in 2016)

- Macomb County Veteran Millage: 0.4 mills (2008-present; increase approved in 2016)

2011

- Recreation Authority of Roseville and Eastpointe: 1 millage (2011-Present)

2012

- Detroit Institute of Arts: 0.2 mills (2012-2022; renewal question on March 2020 ballot)

2015

- South Macomb Oakland Regional Services Authority (SMORSA): 14 mills (2015-present)

**The Huron Clinton Metropark Authority millage has been levied since the 1940s***

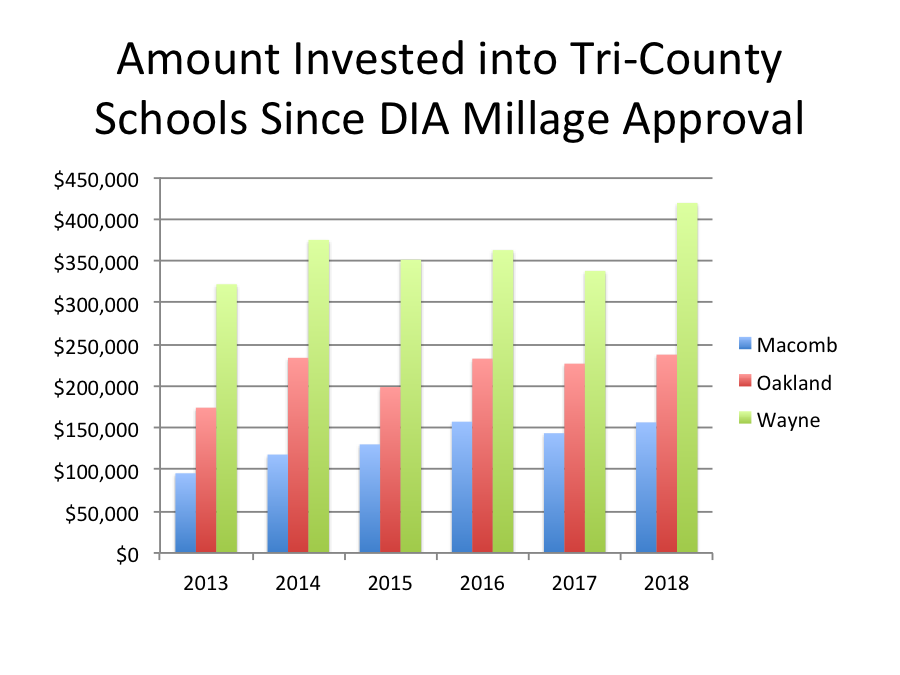

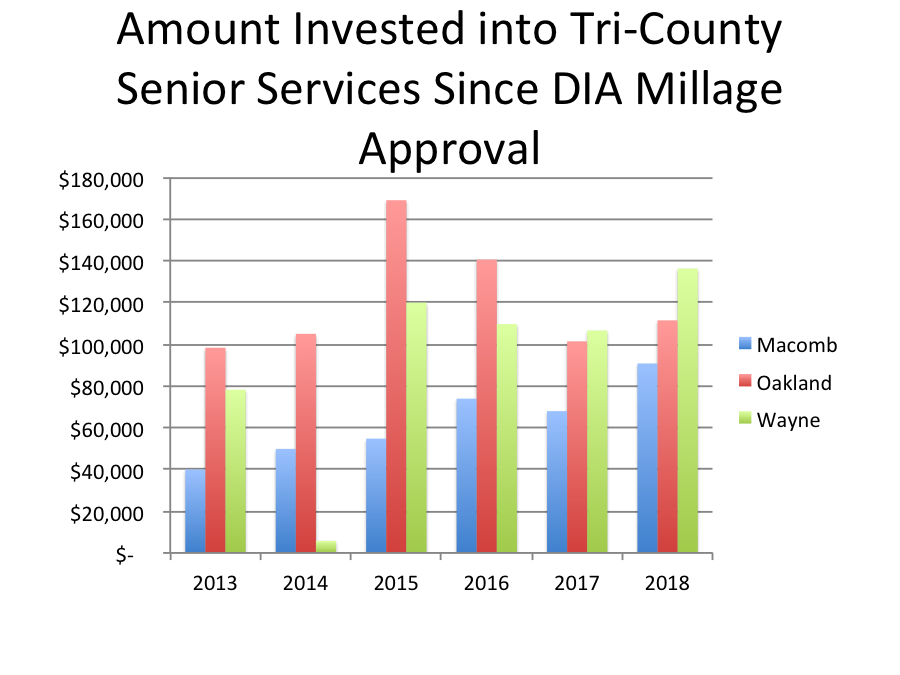

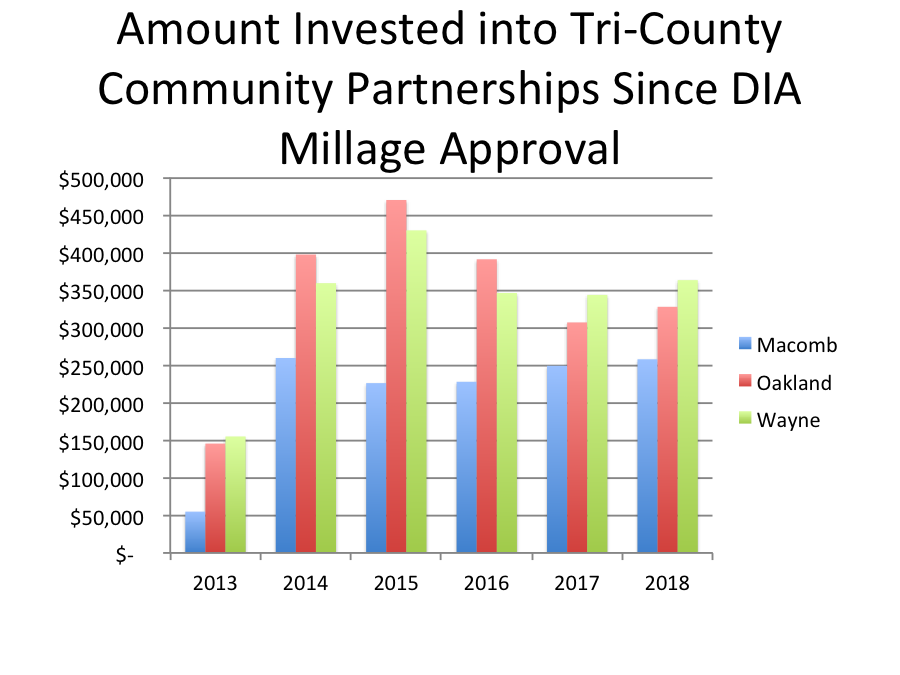

Chart 3

The trend of decreased property values and the addition of special assessments to tax bills continued in the wake of the Great Recession. In 2011, residents in Eastpointe and Roseville approved a 1-mill levy to fund the newly created Recreational Authority of Roseville and Eastpointe (RARE). Later, voters in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties approved a 10-year, 1 mill tax for the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), which appeared on tax bills in December of 2012. The largest increase came in 2015, when Eastpointe and Hazel Park voters approved the creation of the South Macomb Oakland Regional Services Authority (SMORSA), to provide a new revenue source for public safety services in both cities; this regional authority levies 14 mills annually. Macomb County voters also approved a 0.069 mill veterans millage in 2016, a slight increase from an earlier 0.04 millage rate. In addition, residents of Eastpointe have regularly renewed a millage to support their local library.

Between 1998 and 2019, the timeline for the data in this post, the amount in taxes paid reached a high in 2009 at $2,432.30 (when the taxable value of the property was at its highest) and a low in 2014 at $1,563.50 (when the taxable value was at its lowest). Due to the limitations of Michigan’s Proposal A, which only allows annual taxable value increases of 5 percent or the rate of inflation (unless the property is sold), the taxable value of this hypothetical property rose only about 7.4 percent over the next five years (2015-19). However, due to these new assessments, the hypothetical property owner paid about 38 percent more in total property tax during that timeframe—roughly equal to the rate of the home’s assessed value increase.

Eastpointe’s case reveals that local governments have had some success in combating the fiscal consequences of the decline of general operating tax revenue with voter-approved special assessments for the county-level service authorities, and especially with SMORSA. Voter support for these services has been there in recent years, but it remains to be seen whether it will persist in the coming years.

This year, property owners across Macomb County may see some additional changes to their tax bills. In March, the DIA will ask voters to renew a 10 year, 1 mill tax renewal; if voted down in any particular county, the DIA assessment in that county will fall off the tax rolls in 2022. Voters will also be asked to approve a 1.9, 10-year millage on the March ballot to support classroom operations through the Macomb Intermediate School District (MISD); this proposed millage is different from the general operating millages currently levied by the MISD and local school districts. Later, in August, Macomb County voters will also be asked to approve a millage for a yet to be determined amount and length to support either building a new county jail or renovating the current one. The Regional Transit Authority (RTA) may also be considering a millage proposal in 2020; although at this time it appears Macomb County voters will not be asked to support the proposal to support this.