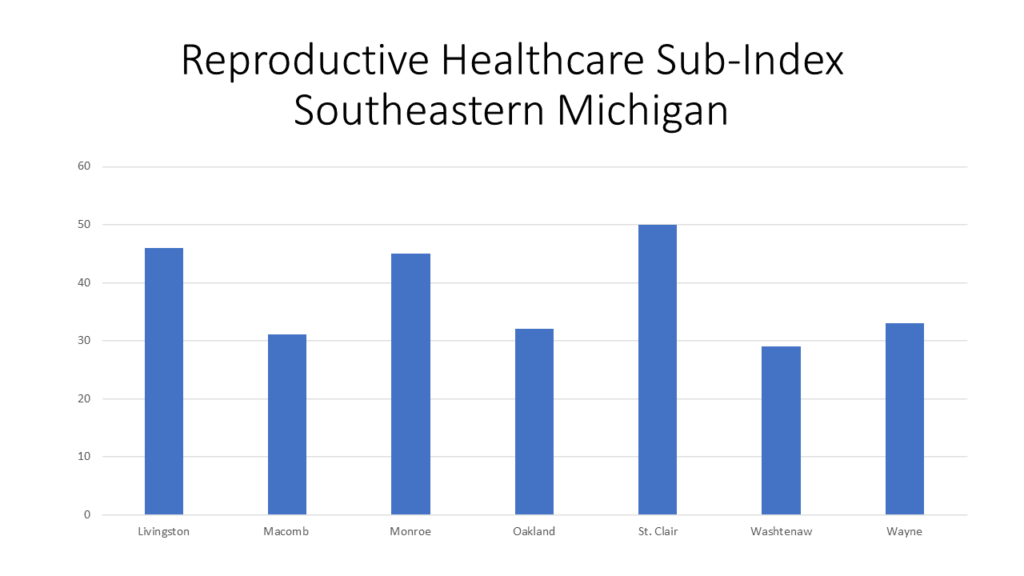

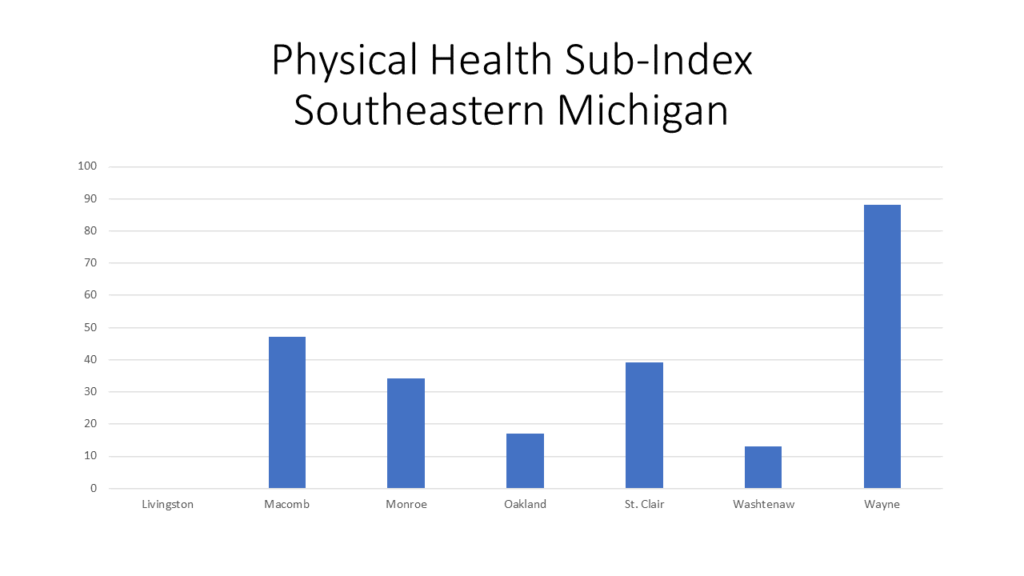

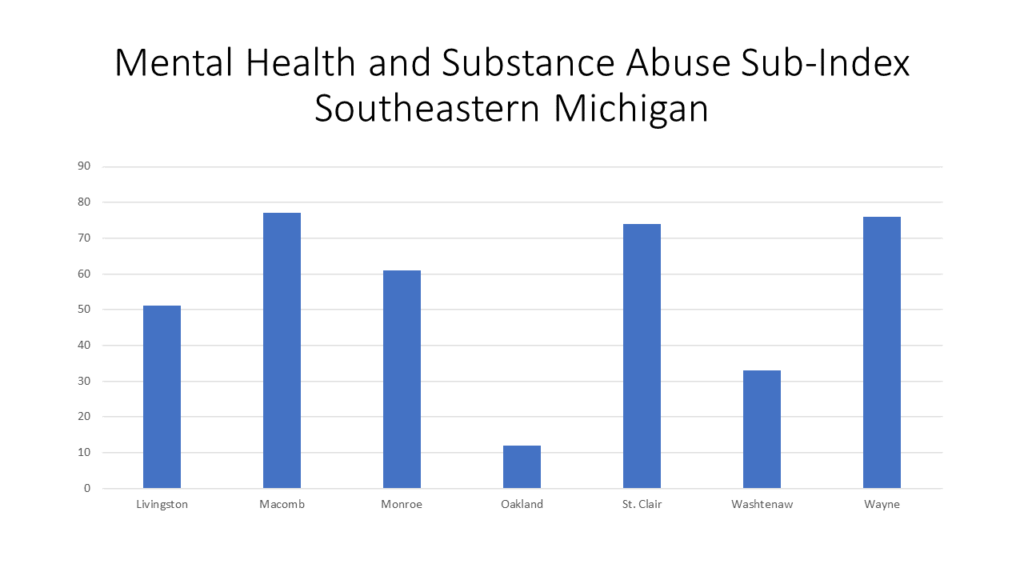

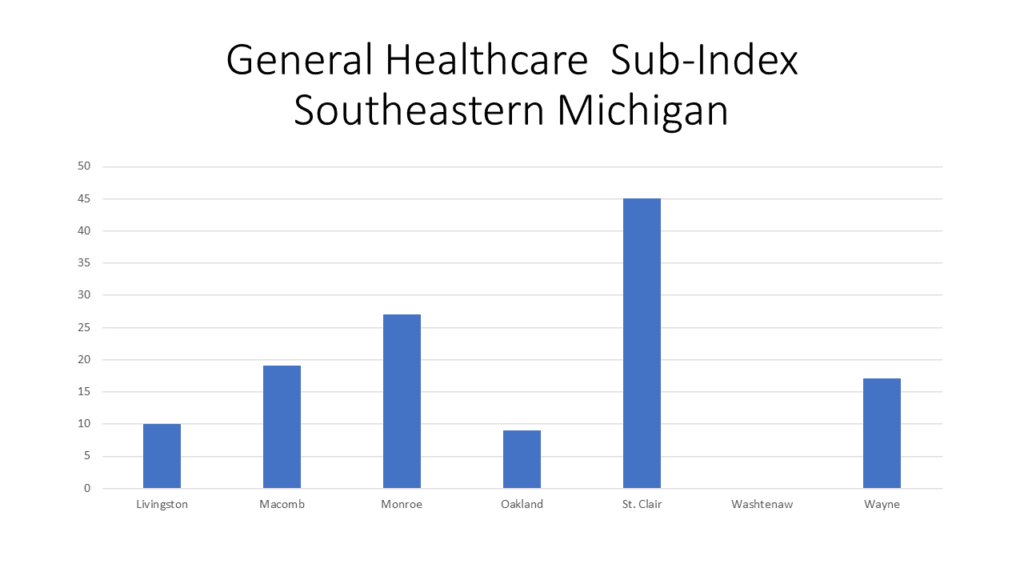

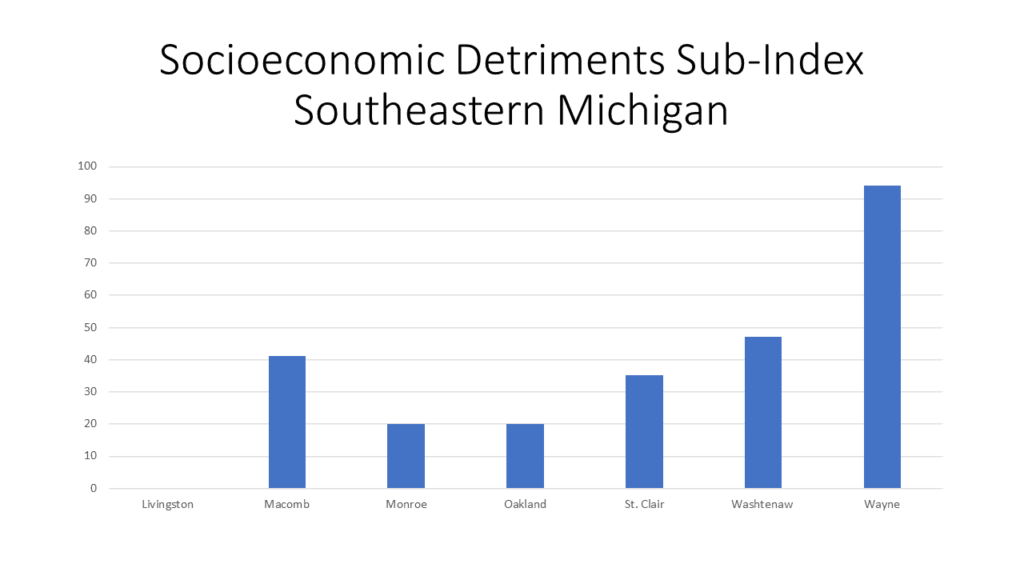

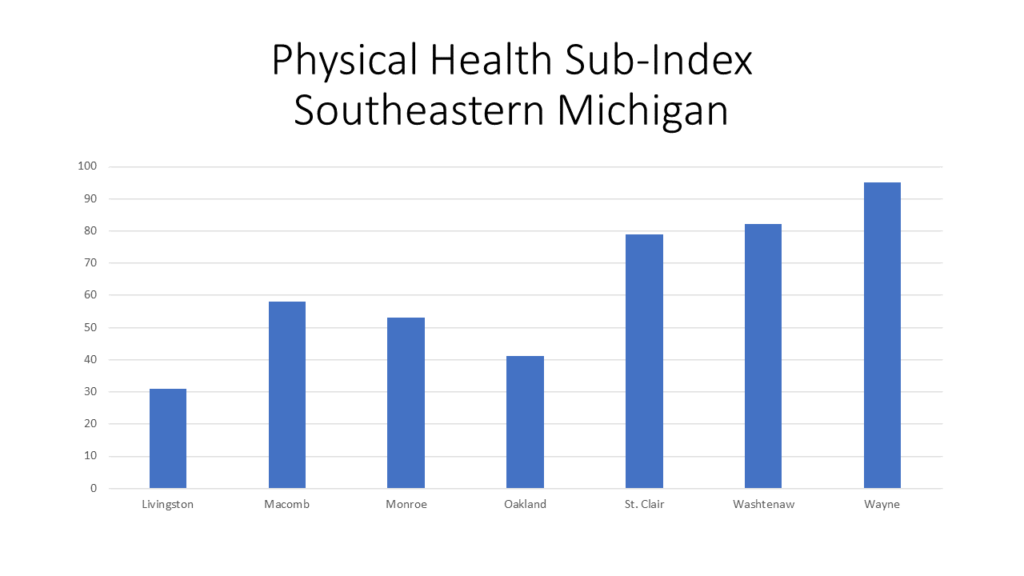

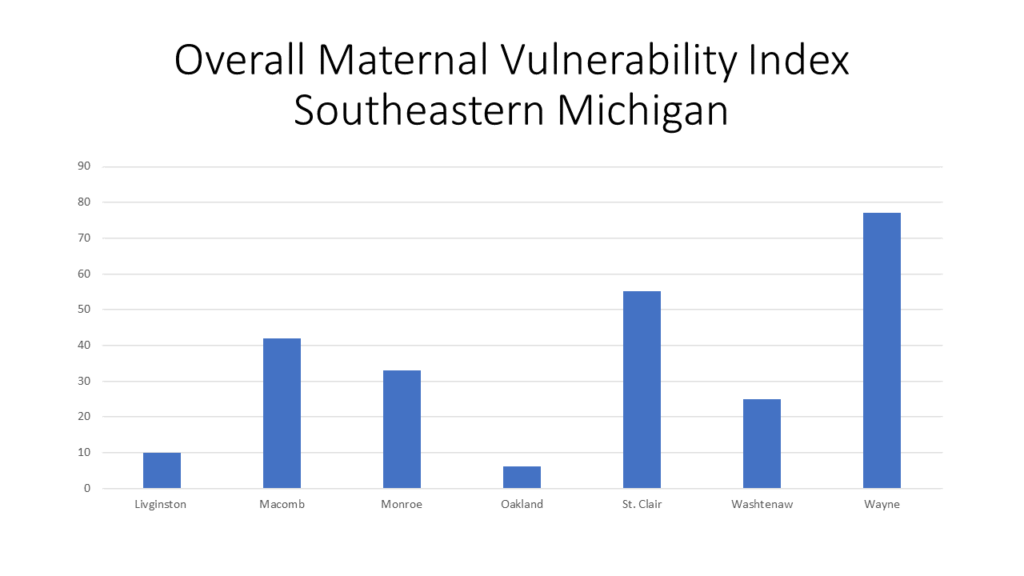

Most recently we explored the Maternal Vulnerability Index (MVI), as created and explained by Surgo Ventures, for Michigan and the seven county Southeastern Michigan region. The six sub-indexes that make up the MVI (Reproductive Healthcare, Physical Health, Mental Health and Substance Abuse, General Healthcare, Socioeconomic Detriments and Physical Environment) are based around factors that include access to healthcare, criminal activity in an area and physical and mental health. The direct data around these factors, and more, directly impact a mother’s health. But, another contributing factor to a mother’s health, both directly and indirectly, is her race. According to the MVI by Surgo Ventures, the Midwest has an MVI average score of 37 out of 100, and the highest vulnerability gap between black women and the regional average. Black women are exposed to a 9 point higher vulnerability score than the regional average, driven by higher exposure to vulnerability based on the following sub-indexes: physical health, mental health and substance abuse, socioeconomic determinants and physical environment.

While the MVI does not examine the vulnerability scores at the county and state level through a racial lens we do know the following.

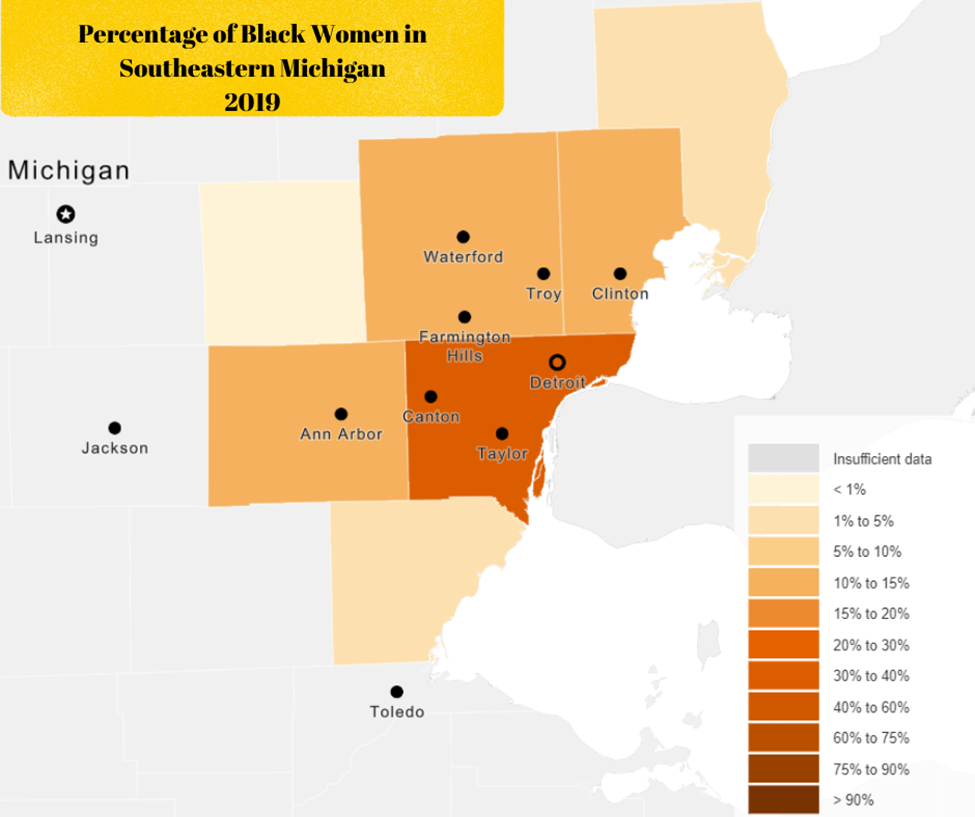

The percentage of the black population in Michigan is 14 percent and the percentage of the black population in Southeastern Michigan is:

- Livingston County: 0.5%

- Macomb County: 12%

- Monroe County: 2%

- Oakland County: 14%

- St. Clair County: 3%

- Washtenaw County: 12%

- Wayne County: 39%

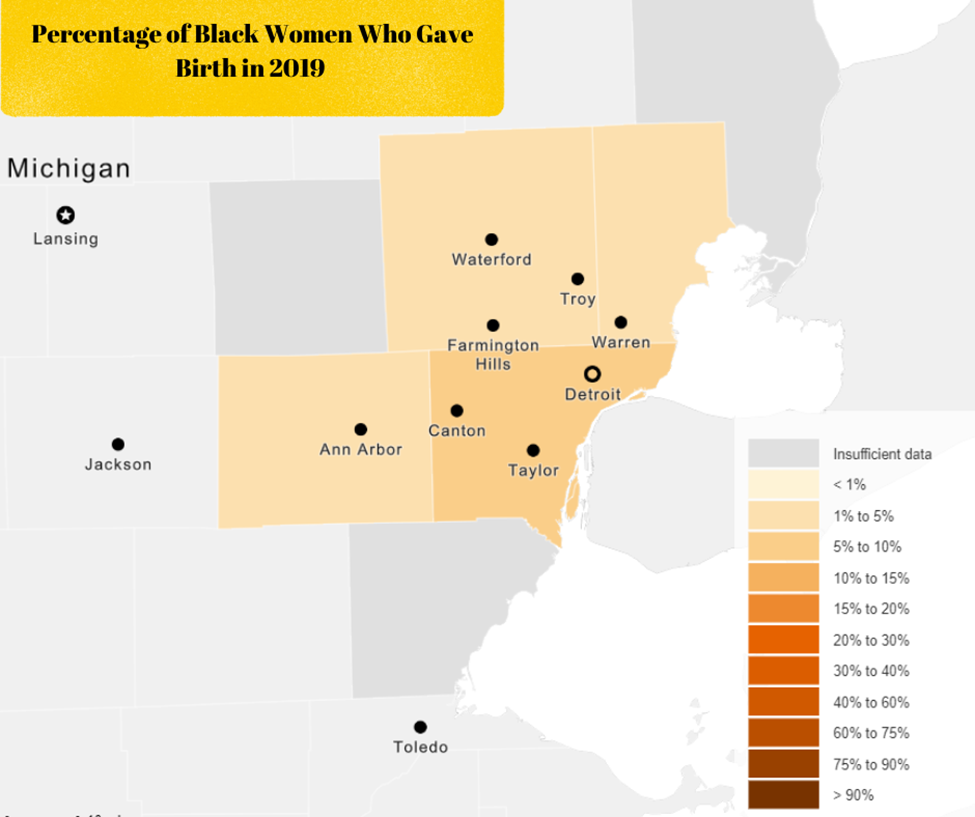

The percent of black women between the ages 15-50 who gave birth in the past 12 months (2019) was:

- Livingston County: NA

- Macomb County: 3%

- Monroe County: 5

- Oakland County: 4%

- St. Clair County: NA

- Washtenaw County: 5%

- Wayne County: 6%

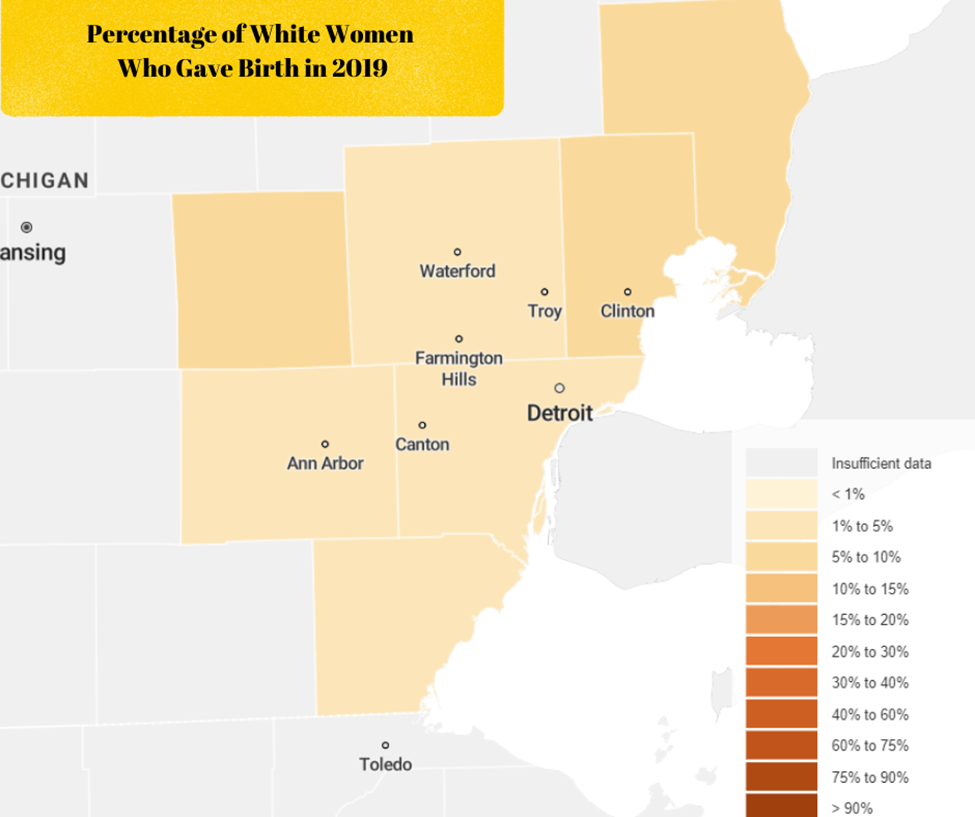

Percent of white women between the ages 15-50 who gave birth in the past 12 months (2019)

- Livingston County: 6%

- Macomb County: 5%

- Monroe County: 5%

- Oakland County: 5%

- St. Clair County: 6%

- Washtenaw County: 4%

- Wayne County: 5%

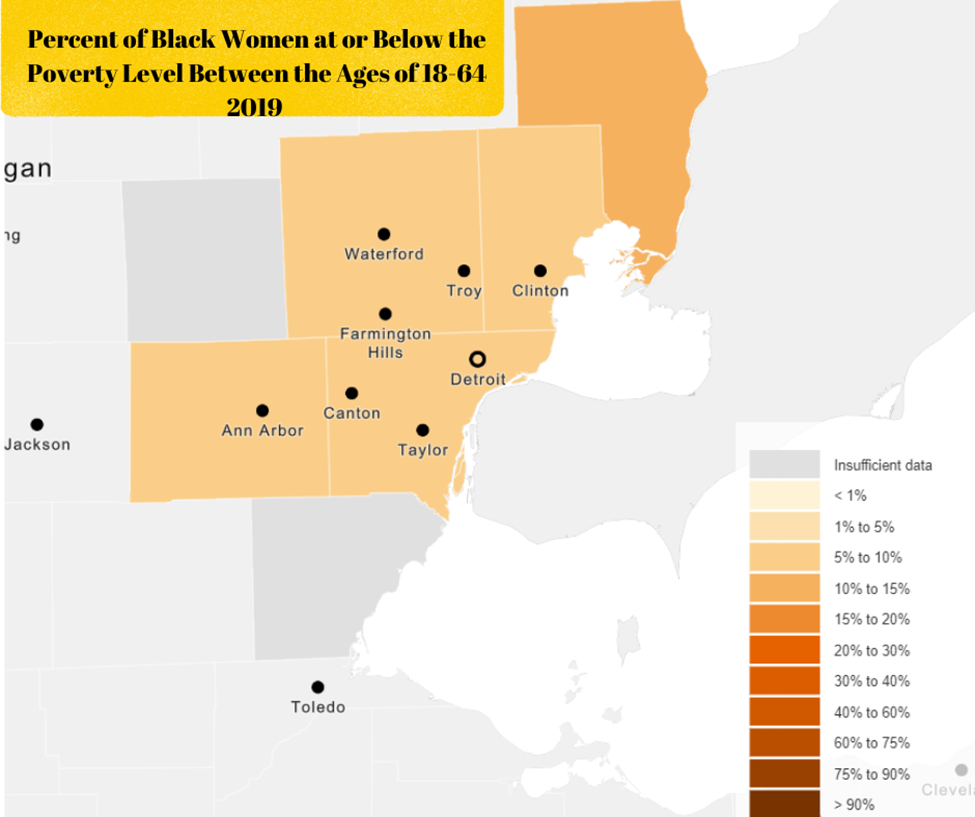

Percent of black women at or below the poverty level between the ages of 18-64 (2019)

- Livingston County: NA

- Macomb County: 5%

- Monroe County: NA

- Oakland County: 6%

- St. Clair County: 13%

- Washtenaw County: 7%

- Wayne County: 9%

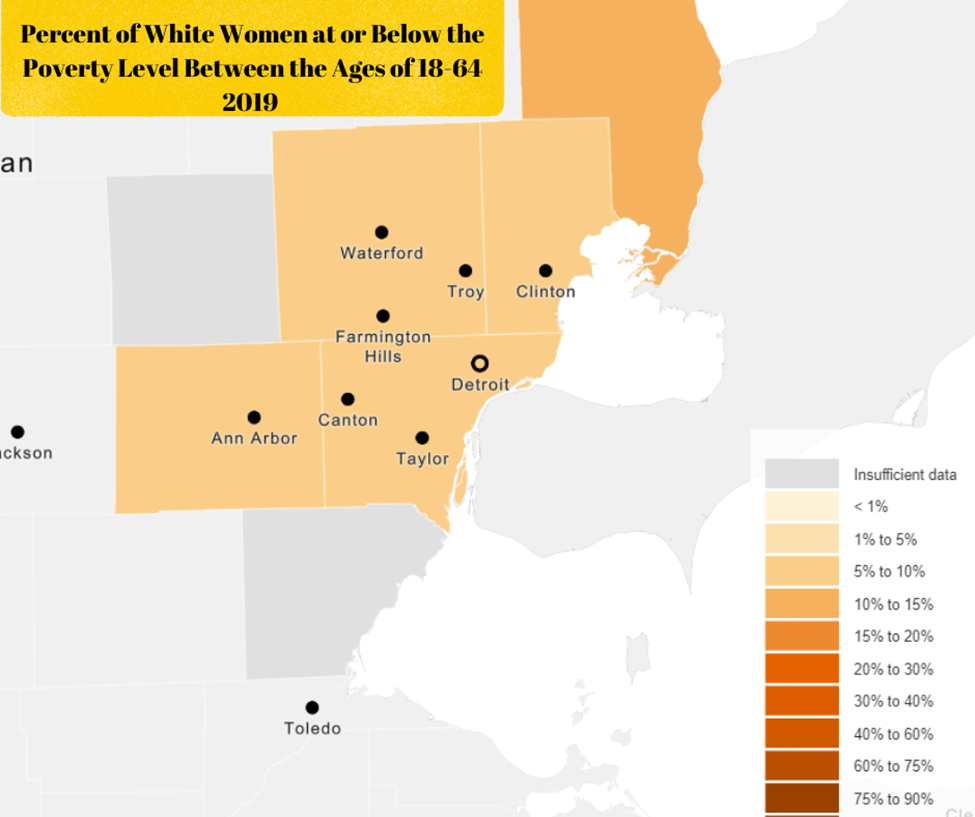

Percent of white women at or below the poverty level between the ages of 18-64 (2019)

- Livingston County: 1%

- Macomb County: 3%

- Monroe County: 4%

- Oakland County: 2%

- St. Clair County: 3%

- Washtenaw County: 4%

- Wayne County: 4%

Furthermore, of the black residents in Southeastern Michigan between the ages of 19 to 64 years of age the following percentage had no health insurance in 2019:

- Livingston County: 4%

- Macomb County: 5%

- Monroe County: 5%

- Oakland County: 4%

- St. Clair County: 4%

- Washtenaw County: 5%

- Wayne County: 6%

Of the white residents in Southeastern Michigan between the ages of 19 to 64 years of age the following percentage had no health insurance in 2019:

- Livingston County: 3%

- Macomb County: 5%

- Monroe County: 3%

- Oakland County: 4%

- St. Clair County: 4%

- Washtenaw County: 3%

- Wayne County: 5%

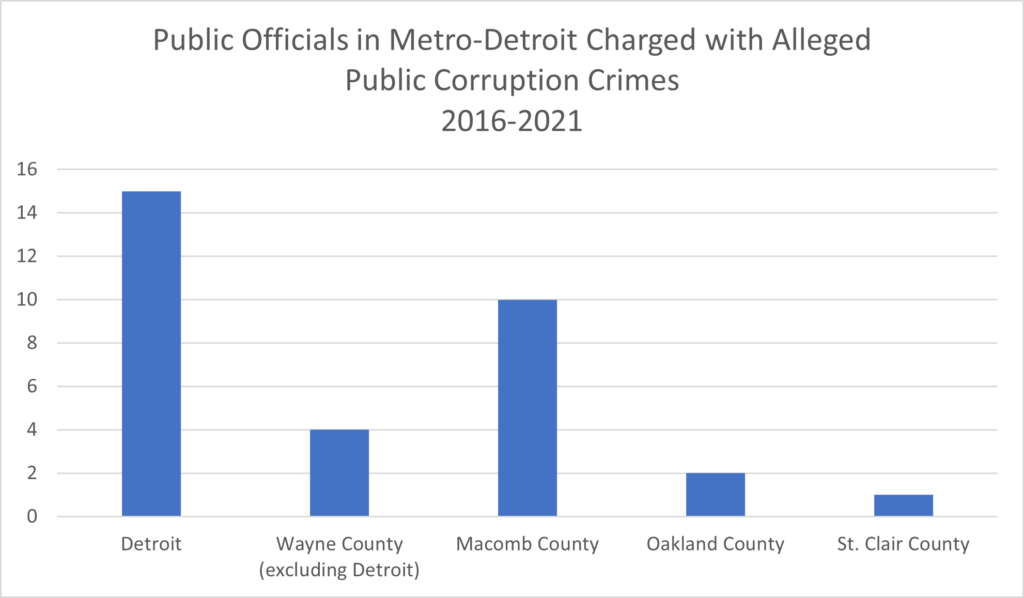

While the numbers don’t very greatly, it does show that while there are fewer black women in Southeastern Michigan there is at least an equal, and in some cases a greater, percentage of them who live in poverty, have had children and who do not have health care. Of course, the MVI also looks at factors such as crime where women live (Wayne County has the highest percentage of black residents in the region and the state and Detroit also has one of the highest crime rates), their access to mental health and addiction services, obesity and diabetes rates. All of these are also factors as to why black women in the Midwest are exposed to a 9 point higher vulnerability score than the regional average, which is 37.